https://www.nginx.com/blog/building-microservices-using-an-api-gateway/

The first article in this seven-part series about designing, building, and deploying microservices introduced the Microservices Architecture pattern. It discussed the benefits and drawbacks of using microservices and how, despite the complexity of microservices, they are usually the ideal choice for complex applications. This is the second article in the series and will discuss building microservices using an API Gateway.

When you choose to build your application as a set of microservices, you need to decide how your application’s clients will interact with the microservices. With a monolithic application there is just one set of (typically replicated, load-balanced) endpoints. In a microservices architecture, however, each microservice exposes a set of what are typically fine-grained endpoints. In this article, we examine how this impacts client-to-application communication and proposes an approach that uses an API Gateway.

Editor’s note – This seven-part series of articles is now complete:

- Introduction to Microservices

- Building Microservices: Using an API Gateway (this article)

- Building Microservices: Inter-Process Communication in a Microservices Architecture

- Service Discovery in a Microservices Architecture

- Event-Driven Data Management for Microservices

- Choosing a Microservices Deployment Strategy

- Refactoring a Monolith into Microservices

Introduction

Let’s imagine that you are developing a native mobile client for a shopping application. It’s likely that you need to implement a product details page, which displays information about any given product.

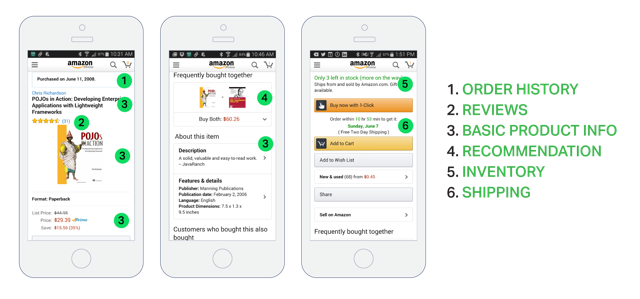

For example, the following diagram shows what you will see when scrolling through the product details in Amazon’s Android mobile application.

Even though this is a smartphone application, the product details page displays a lot of information. For example, not only is there basic product information (such as name, description, and price) but this page also shows:

- Number of items in the shopping cart

- Order history

- Customer reviews

- Low inventory warning

- Shipping options

- Various recommendations, including other products this product is frequently bought with, other products bought by customers who bought this product, and other products viewed by customers who bought this product

- Alternative purchasing options

When using a monolithic application architecture, a mobile client would retrieve this data by making a single REST call (GET api.company.com/productdetails/productId) to the application. A load balancer routes the request to one of N identical application instances. The application would then query various database tables and return the response to the client.

In contrast, when using the microservices architecture the data displayed on the product details page is owned by multiple microservices. Here are some of the potential microservices that own data displayed on the example product details page:

- Shopping Cart Service – Number of items in the shopping cart

- Order Service – Order history

- Catalog Service – Basic product information, such as its name, image, and price

- Review Service – Customer reviews

- Inventory Service – Low inventory warning

- Shipping Service – Shipping options, deadlines, and costs drawn separately from the shipping provider’s API

- Recommendation Service(s) – Suggested items

We need to decide how the mobile client accesses these services. Let’s look at the options.

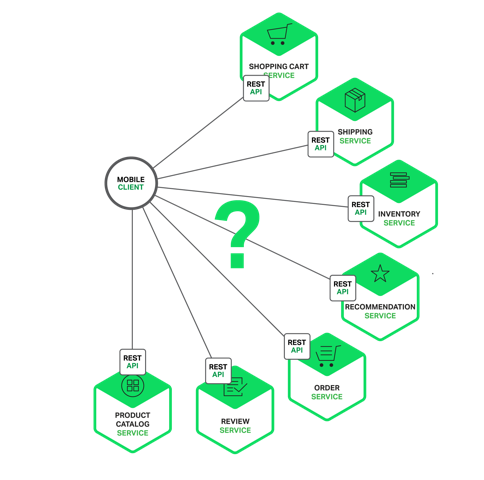

Direct Client-to-Microservice Communication

In theory, a client could make requests to each of the microservices directly. Each microservice would have a public endpoint (https://serviceName.api.company.name). This URL would map to the microservice’s load balancer, which distributes requests across the available instances. To retrieve the product details, the mobile client would make requests to each of the services listed above.

Unfortunately, there are challenges and limitations with this option. One problem is the mismatch between the needs of the client and the fine-grained APIs exposed by each of the microservices. The client in this example has to make seven separate requests. In more complex applications it might have to make many more. For example, Amazon describes how hundreds of services are involved in rendering their product page. While a client could make that many requests over a LAN, it would probably be too inefficient over the public Internet and would definitely be impractical over a mobile network. This approach also makes the client code much more complex.

Another problem with the client directly calling the microservices is that some might use protocols that are not web-friendly. One service might use Thrift binary RPC while another service might use the AMQP messaging protocol. Neither protocol is particularly browser- or firewall-friendly and is best used internally. An application should use protocols such as HTTP and WebSocket outside of the firewall.

Another drawback with this approach is that it makes it difficult to refactor the microservices. Over time we might want to change how the system is partitioned into services. For example, we might merge two services or split a service into two or more services. If, however, clients communicate directly with the services, then performing this kind of refactoring can be extremely difficult.

Because of these kinds of problems it rarely makes sense for clients to talk directly to microservices.

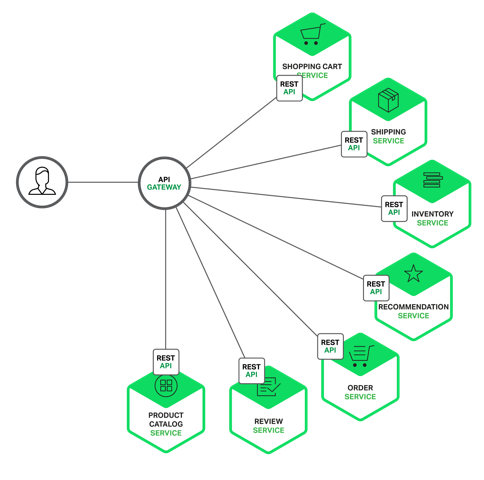

Using an API Gateway

Usually a much better approach is to use what is known as an API Gateway. An API Gateway is a server that is the single entry point into the system. It is similar to the Facade pattern from object-oriented design. The API Gateway encapsulates the internal system architecture and provides an API that is tailored to each client. It might have other responsibilities such as authentication, monitoring, load balancing, caching, request shaping and management, and static response handling.

The following diagram shows how an API Gateway typically fits into the architecture:

The API Gateway is responsible for request routing, composition, and protocol translation. All requests from clients first go through the API Gateway. It then routes requests to the appropriate microservice. The API Gateway will often handle a request by invoking multiple microservices and aggregating the results. It can translate between web protocols such as HTTP and WebSocket and web-unfriendly protocols that are used internally.

The API Gateway can also provide each client with a custom API. It typically exposes a coarse-grained API for mobile clients. Consider, for example, the product details scenario. The API Gateway can provide an endpoint (/productdetails?productid=xxx) that enables a mobile client to retrieve all of the product details with a single request. The API Gateway handles the request by invoking the various services – product info, recommendations, reviews, etc. – and combining the results.

A great example of an API Gateway is the Netflix API Gateway. The Netflix streaming service is available on hundreds of different kinds of devices including televisions, set-top boxes, smartphones, gaming systems, tablets, etc. Initially, Netflix attempted to provide a one-size-fits-all API for their streaming service. However, they discovered that it didn’t work well because of the diverse range of devices and their unique needs. Today, they use an API Gateway that provides an API tailored for each device by running device-specific adapter code. An adapter typically handles each request by invoking on average six to seven backend services. The Netflix API Gateway handles billions of requests per day.

Benefits and Drawbacks of an API Gateway

As you might expect, using an API Gateway has both benefits and drawbacks. A major benefit of using an API Gateway is that it encapsulates the internal structure of the application. Rather than having to invoke specific services, clients simply talk to the gateway. The API Gateway provides each kind of client with a specific API. This reduces the number of round trips between the client and application. It also simplifies the client code.

The API Gateway also has some drawbacks. It is yet another highly available component that must be developed, deployed, and managed. There is also a risk that the API Gateway becomes a development bottleneck. Developers must update the API Gateway in order to expose each microservice’s endpoints. It is important that the process for updating the API Gateway be as lightweight as possible. Otherwise, developers will be forced to wait in line in order to update the gateway. Despite these drawbacks, however, for most real-world applications it makes sense to use an API Gateway.

Implementing an API Gateway

Now that we have looked at the motivations and the trade-offs for using an API Gateway, let’s look at various design issues you need to consider.

Performance and Scalability

Only a handful of companies operate at the scale of Netflix and need to handle billions of requests per day. However, for most applications the performance and scalability of the API Gateway is usually very important. It makes sense, therefore, to build the API Gateway on a platform that supports asynchronous, non-blocking I/O. There are a variety of different technologies that can be used to implement a scalable API Gateway. On the JVM you can use one of the NIO-based frameworks such Netty, Vertx, Spring Reactor, or JBoss Undertow. One popular non-JVM option is Node.js, which is a platform built on Chrome’s JavaScript engine. Another option is to use NGINX Plus. NGINX Plus offers a mature, scalable, high-performance web server and reverse proxy that is easily deployed, configured, and programmed. NGINX Plus can manage authentication, access control, load balancing requests, caching responses, and provides application-aware health checks and monitoring.

Using a Reactive Programming Model

The API Gateway handles some requests by simply routing them to the appropriate backend service. It handles other requests by invoking multiple backend services and aggregating the results. With some requests, such as a product details request, the requests to backend services are independent of one another. In order to minimize response time, the API Gateway should perform independent requests concurrently. Sometimes, however, there are dependencies between requests. The API Gateway might first need to validate the request by calling an authentication service, before routing the request to a backend service. Similarly, to fetch information about the products in a customer’s wish list, the API Gateway must first retrieve the customer’s profile containing that information, and then retrieve the information for each product. Another interesting example of API composition is the Netflix Video Grid.

Writing API composition code using the traditional asynchronous callback approach quickly leads you to callback hell. The code will be tangled, difficult to understand, and error-prone. A much better approach is to write API Gateway code in a declarative style using a reactive approach. Examples of reactive abstractions include Future in Scala, CompletableFuture in Java 8, and Promise in JavaScript. There is also Reactive Extensions (also called Rx or ReactiveX), which was originally developed by Microsoft for the .NET platform. Netflix created RxJava for the JVM specifically to use in their API Gateway. There is also RxJS for JavaScript, which runs in both the browser and Node.js. Using a reactive approach will enable you to write simple yet efficient API Gateway code.

Service Invocation

A microservices-based application is a distributed system and must use an inter-process communication mechanism. There are two styles of inter-process communication. One option is to use an asynchronous, messaging-based mechanism. Some implementations use a message broker such as JMS or AMQP. Others, such as Zeromq, are brokerless and the services communicate directly. The other style of inter-process communication is a synchronous mechanism such as HTTP or Thrift. A system will typically use both asynchronous and synchronous styles. It might even use multiple implementations of each style. Consequently, the API Gateway will need to support a variety of communication mechanisms.

Service Discovery

The API Gateway needs to know the location (IP address and port) of each microservice with which it communicates. In a traditional application, you could probably hardwire the locations, but in a modern, cloud-based microservices application this is a non-trivial problem. Infrastructure services, such as a message broker, will usually have a static location, which can be specified via OS environment variables. However, determining the location of an application service is not so easy. Application services have dynamically assigned locations. Also, the set of instances of a service changes dynamically because of autoscaling and upgrades. Consequently, the API Gateway, like any other service client in the system, needs to use the system’s service discovery mechanism: either Server‑Side Discovery or Client‑Side Discovery. A later article will describe service discovery in more detail. For now, it is worthwhile to note that if the system uses Client-Side Discovery then the API Gateway must be able to query the Service Registry, which is a database of all microservice instances and their locations.

Handling Partial Failures

Another issue you have to address when implementing an API Gateway is the problem of partial failure. This issue arises in all distributed systems whenever one service calls another service that is either responding slowly or is unavailable. The API Gateway should never block indefinitely waiting for a downstream service. However, how it handles the failure depends on the specific scenario and which service is failing. For example, if the recommendation service is unresponsive in the product details scenario, the API Gateway should return the rest of the product details to the client since they are still useful to the user. The recommendations could either be empty or replaced by, for example, a hardwired top ten list. If, however, the product information service is unresponsive then API Gateway should return an error to the client.

The API Gateway could also return cached data if that was available. For example, since product prices change infrequently, the API Gateway could return cached pricing data if the pricing service is unavailable. The data can be cached by the API Gateway itself or be stored in an external cache such as Redis or Memcached. By returning either default data or cached data, the API Gateway ensures that system failures do not impact the user experience.

Netflix Hystrix is an incredibly useful library for writing code that invokes remote services. Hystrix times out calls that exceed the specified threshold. It implements a circuit breaker pattern, which stops the client from waiting needlessly for an unresponsive service. If the error rate for a service exceeds a specified threshold, Hystrix trips the circuit breaker and all requests will fail immediately for a specified period of time. Hystrix lets you define a fallback action when a request fails, such as reading from a cache or returning a default value. If you are using the JVM you should definitely consider using Hystrix. And, if you are running in a non-JVM environment, you should use an equivalent library.

Summary

For most microservices-based applications, it makes sense to implement an API Gateway, which acts as a single entry point into a system. The API Gateway is responsible for request routing, composition, and protocol translation. It provides each of the application’s clients with a custom API. The API Gateway can also mask failures in the backend services by returning cached or default data. In the next article in the series, we will look at communication between services.

Editor’s note – This seven-part series of articles is now complete:

- Introduction to Microservices

- Building Microservices: Using an API Gateway (this article)

- Building Microservices: Inter-Process Communication in a Microservices Architecture

- Service Discovery in a Microservices Architecture

- Event-Driven Data Management for Microservices

- Choosing a Microservices Deployment Strategy

- Refactoring a Monolith into Microservices

Guest blogger Chris Richardson is the founder of the original CloudFoundry.com, an early Java PaaS (Platform as a Service) for Amazon EC2. He now consults with organizations to improve how they develop and deploy applications. He also blogs regularly about microservices at http://microservices.io.