webpack- why and how

首先不要被webpack做的复杂花哨的工作所迷惑,到底webpack是个啥?一句话,webpack是一个module bundler(模块打包器)。多一句话,webpack通过将多个js文件或者其他assets整合进一个大的bundle.js文件中,允许我们在浏览器中使用javascript module功能。而所有类似翻译es6/es7为es5,或者使用css module功能仅仅为webpack提供的一些额外功能。但是我们永远不要忘记其核心功能:一个允许在浏览器中使用js模块的打包器

由于webpack有着非常强大的plugin/loader生态系统,这往往使得初学者眼花缭乱,从而对webpack是什么这个核心问题有些糊涂,因为webpack貌似无所不能,能做太多太多。虽然透过plugin机制我们获得了很多重要的功能本身是很棒的,但是我们还是应该聚焦一下:为什么webpack会存在:module bunlding.

webpack是一个命令行工具,用于生成由code和其他file组成的bunldle。webpack本身并不运行于server或者说browser,webpack命令行工具只运行于web app的构建过程。webpack从一个entry.js文件开始,将其依赖的所有js或者其他assets(通过loader)打包成一个巨大的文件。

随后这个大文件将被从server传递到客户端浏览器运行。注意:browser和server并不会关心该文件是否由webpack所生成,browser/server将该bundle文件当作其他文件一样来看待和处理。

webpack-dev-server vs webpack cli

webpack-dev-server是一个和webpack-cli不同的工具,它是一个基于node/express的dev server.当该server运行时,我们实际上从该server的一个端口下load app(bundle)并在浏览器中运行。当然该server还能提供其他一些非常棒的功能,比如Hot module reloading.

Why

传统server rendered app

传统的web app实际上是server端渲染的页面,这意味着浏览器仅仅是一个html浏览器,所有的逻辑都存在于server端。server端将一个静态的html页面传回客户端浏览器,浏览器只负责渲染静态的html/css.这也是为什么当你导航在server rendered app的不同页面时浏览器总会刷新的原因。

Spa: single page app

自从js ajax兴起后,单页应用就开始慢慢崛起,因为它的无刷新特性给与了很棒的用户体验。

Dynamic Spas mean more code in the browser

当我们说dynamic时我们是指有越来越多的以javascript形式存在的logic运行于浏览器中。而我们server side render apps仅会吐出一些并非dynamic的static page,这时所谓的dynamic仅发生在server端用于产生这个static page,而一旦该page产生并且传递到browser了,就基本上是静态的了(因为并没有很多的javascript代码)

How

如何管理越来越多的浏览器端逻辑是一个重要挑战,而webpack就是为了应对这种web开发越来越多逻辑从服务端向客户端转移的现状的。。。

那么,我们要问,为什么spa单页应用就会称为问题呢?

一个很重要的原因是:我们需要将复杂的js代码劈成更小的文件以便app更好的工作。

我们可以将所有逻辑写成一个js文件,然而,可以想象这将称为开发者的噩梦。没有人能知道应用是如何工作的,想开发新的功能难于上青天。这时,我们就需要将复杂的逻辑分到不同的chunk中,也就是根据功能划分将逻辑划分到多个js文件中去。这就是一个“模块化”的开发模式。

你可能又会想,那我们就把一个大的文件打散成多个js文件呗。。但问题是浏览器并不知道这些文件之间的依赖关系,因此我们需要一个模块管理工具,以便在浏览器端支持模块化。这就是webpack/browserfy带来的价值。

在server端node环境中,支持内置的module resolver,我们可以require一个module来使用它,然而浏览器并不具备这个require一个module的能力,也就是说browser是不懂require,import的!

https://adamisntdead.com/lets-write-a-module-bundler/

咱们直接上一个网上找的最简单的bundler代码,了解下具体工作原理

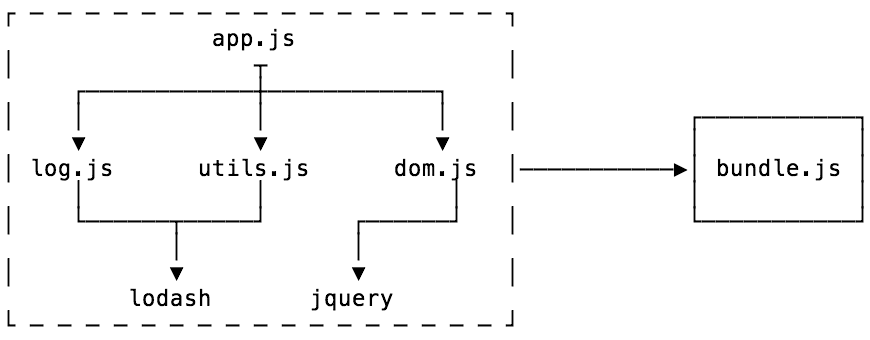

// Hello! Welcome, welcome, it's great to have you here! // Today we're going to be building a really simple Javascript module // bundler! // // Before we start, I want to give a few acknowledgements, for which this // source is heavily based on. // // * Unbundling the JavaScript module bundler - Luciano Mammino // http://loige.link/bundle-dublinjs // // * Minipack - Ronen Amiel // https://github.com/ronami/minipack // // Okay, lets get started! // // Let's start with what a module bundler actually is. // // You may have used tools such as browserify, webpack, rollup or one of // many others, but a module bundler is a tool that takes pieces of // javascript and takes them and their dependencies and makes it into a // single file, usually for use in the browser. // // It usually starts with an entry file, and from their bundles up all of // the code needed for that entry file. // // + - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + // app.js // | + | // +------------+------------+ // | | | | | +-----------+ // v v v | | // | log.js utils.js dom.js |----------->| bundle.js | // | | | | | // | +------+-----+ +------+ | +-----------+ // | | // | v v | // lodash jquery // + - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + // // There are 2 main stages of a bundler: // // 1. Dependency resolution // 2. Packing // // Starting from an entry point (above it's `main.js`), the goal of // dependency resolution is to look for all of the dependencies of your // code - that is, other pieces of code that it needs to function - and // construct a graph (called a dependency graph) like the above. // // Once this is done, you can then pack, or convert your dependency graph // into a single file that you can use. // Let's start out our code with some imports (I will give the reasoning // later) const detective = require('detective') const resolve = require('resolve').sync const fs = require('fs') const path = require('path') // The first thing we have to do is think up how we want to represent a // module during the dependency resolution phase. // We are going to need four things: // // * The name and an identifier of the file // * Where the file came from (in the file system) // * The code in the file // * What dependencies that file needs. // // The graph structure gets built up through the recursive 'what // dependencies' question. // // In Javascript, the easiest way to represent such a set of data would // be an object, so thats what's gonna happen. let ID = 0 function createModuleObject(filepath) { const source = fs.readFileSync(filepath, 'utf-8') const requires = detective(source) const id = ID++ return { id, filepath, source, requires } } // // Looking at this `createDependencyObject` function, the notable part // is the call to a function called `detective`. // // Detective is a library that can "Find all calls to require() no // matter how deeply nested", and using it means we can avoid doing our // own AST traversal! // // One thing to note (and this is the same in almost all module // bundlers), if you try to do something weird like // // ``` // const libName = 'lodash' // const lib = require(libName) // ``` // // It will not be able to find it (because that would mean executing the // code). // So what does running this function on the path of a module give? // // // { // ╭-----------------------------------╮ id: 0, // | ◎ ○ ○ app.js | filepath: '/Users/john/app.js', // +-----------------------------------+ requires: [ './log', './utils' ], // | const log = require('./logging') | source: ` // | const util = require('./utils') | const log = require('./logging') // | +----> const util = require('./utils') // | log('hello world!') | // | | log('hello world!') // | | ` // +-----------------------------------+ } // // Whats next? // Dependency resolution!!1!11!!!1! // // Okay, not quite yet - I first want to talk about a thing called a // module map. // // When you import modules in node, you can do relative imports, like // `require('./utils')`. So when your code calls this, how does the // bundler know what is the right './utils' file when everything is // packaged? // // That is the problem the module map solves. // // Our module object has a unique `id` key which will be our 'source of // truth'. So when we are doing our dependency resolution, for each // module, we will keep a list of the names of what is being required // along with their id, so we can get the correct module at runtime. // // This also means we can store all of the modules in a non-nested // object, using the id as a key! // // // // +-------------+ +-----------+ // | Modules Map | | Modules | // +----+-----------+-+---+ +-----+-----------+----+ // +--+--->./utils | 2 <+--+ | 2 | { ... } | // | +----------------+-----+ | +-----+----------------+ // | | ./logger | 3 | | | 3 | { ... } | // | +----------------+-----+ | +-----+----------------+ // | | moment | 4 | | | 3 | { ... } | // | +----------------+-----+ | +-----+----------------+ // | | ... | ... | | | ... | ... | // | +----------------+-----+ | +-----+----------------+ // | | // | | // argument to module // require object's id function getModules(entry) { const rootModule = createModuleObject(entry) const modules = [rootModule] // Iterate over the modules, even when new // ones are being added for (const module of modules) { module.map = {} // Where we will keep the module maps module.requires.forEach(dependency => { const basedir = path.dirname(module.filepath) const dependencyPath = resolve(dependency, { basedir }) const dependencyObject = createModuleObject(dependencyPath) module.map[dependency] = dependencyObject.id modules.push(dependencyObject) }) } return modules } // Okay, so there is a fair amount going on in the `getModules` // function. // It's main purpose is to start at the root/entry module, and look for // and resolve dependencies recursively. // // What do I mean by 'resolve dependencies'? // In node there is a thing called the `require.resolve`, and it's how // node figures out where the file that you are requiring is. This is // because we can import relatively or from a `node_modules` folder. // // Lucky for us, there's an npm module named `resolve` which implements // this algorithm for us! We just have to pass in the argument that // would be for require and the base url, and it will do all the hard // work for us :) // // So we are doing this resolution for each dependency of each module in // the project. // // We are also creating that modules map `map` that I mentioned earlier. // // At the end of the function, we are left with an array named `modules` // which will contain module objects for every module/dependency in our // project! // // Now that we have that, we can move on to the final step, packing! // In the browser there is no such thing as modules (kind of), but that // means there is no require function, and no `module.exports`, so even // though we have all of our dependencies, we currently have no way to // use them as modules. // // Enter the factory function. // A factory function is a function (that's not a constructor) which // returns an object. // It is a pattern from object oriented programming, and one of its uses // is to do encapsulation and dependency injection. // // Sound good? // // Using a factory function, we can both inject our own `require` // function and `module.exports` object that can be used in our bundled // code and give the module it's own scope. // // +-------------------------------+ // | Factory Function | // +-------------------------------+ // | | // | (require, module) => { | // | /* Module source */ | // | } | // +-------------------------------+ // // I am now going to show you the `pack` function, and I will explain // the rest after. function pack(modules) { const modulesSource = modules.map(module => `${module.id}: { factory: (module, require) => { ${module.source} }, map: ${JSON.stringify(module.map)} }` ).join() return `(modules => { const require = id => { const { factory, map } = modules[id] const localRequire = name => require(map[name]) const module = { exports: {} } factory(module, localRequire) return module.exports } require(0) })({ ${modulesSource} })` } // Most of that is just template literals of javascript, so let's // discuss what it's doing. // // First up is `modulesSource`. Here, we are going through each of the // modules and transforming it into a string of source. // So what is the output like for a module object? // // { // id: 0, 0: { // filepath: '/Users/john/app.js', factory: (module, require) => { // requires: [ './log', './utils' ], const log = require('./logging') // map: { './log': 1, './utils': 2 } const util = require('./utils') // source: ` ----> // const log = require('./logging') log('hello world!') // const util = require('./utils') }, // map: { './log': 1, './utils': 2 } // log('hello world!') } // ` // } // // Now it's a little hard to read, but you can see that the source is // encapsulated and we are providing `modules` and `require` using the // factory function as I mentioned before. // // We are also including the modules map that we constructed during the // dependency resolution. // // Next in the function we join all of these up to create a big object // of all the dependencies. // The next string of code is an IIFE, which means when you run that // code in the browser (or anywhere else), the function will be ran // immediately. IIFE is another pattern for encapsulating scope, and is // used here to so we don't polute the global scope with our `require` // and `modules. // You can see that we are defining two require functions, `require` and // `localRequire`. // // Require accepts the id of a module object, but of course the source // code isn't written using ids, we are using the other function // `localRequire` to take any arguments to require by the modules and // convert them to the correct id. // This is using those module maps! // // After this, we are defining a `module object` that the module can // populate, and passing both functions into the factory, after which we // return `module.exports`. // // Lastly, we call `require(0)` to require the module with an id of 0, // being our entry file. // // And thats it! // That is our module bundler 100% complete! module.exports = entry => pack(getModules(entry)) // So we now have a working module bundler. // // Now this probably shouldn't be used in production, because it's // missing loads of features (like managing circular dependency, making // sure each file gets only parsed once, es-modules etc...) but has // hopefully given you a good idea on how module bundlers actually work. // // In fact, this one works in about 60 lines if you remove all of the // source code! // // Thanks for reading and I hope you have enjoyed a look into the // workings of our simple module bundler!

webpack bundle.js代码解读

http://www.cnblogs.com/venoral/p/6102976.html

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/40562031/webpack-how-does-webpack-work