对于并发操作,前面我们已经了解到了 channel 通道、同步原语 sync 包对共享资源加锁、Context 跟踪协程/传参等,这些都是并发编程比较基础的元素,相信你已经有了很好的掌握。今天我们介绍下如何使用这些基础元素组成并发模式,更好的编写并发程序。

for select 无限循环模式

这个模式比较常见,之前文章中的示例也使用过,它一般是和 channel 组合完成任务,格式为:

for { //for 无限循环,或者使用 for range 循环

select {

//通过 channel 控制

case <-done:

return

default:

//执行具体的任务

}

}

- 这种是 for + select 多路复用的并发模式,哪个 case 满足条件就执行对应的分支,直到有满足退出的条件,才会退出循环。

- 没有退出条件满足时,则会一直执行 default 分支

for range select 有限循环模式

for _,s:=range []int{}{

select {

case <-done:

return

case resultCh <- s:

}

- 一般把迭代的内容发送到 channel 上

- done channel 用于退出 for 循环

- resultCh channel 用来接收循环的值,这些值可以通过 resultCh 传递给其他调用者

select timeout 模式

假如一个请求需要访问服务器获取数据,但是可能因为网络问题而迟迟获取不到响应,这时候就需要设置一个超时时间:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

result := make(chan string)

timeout := time.After(3 * time.Second) //

go func() {

//模拟网络访问

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

result <- "服务端结果"

}()

for {

select {

case v := <-result:

fmt.Println(v)

case <-timeout:

fmt.Println("网络访问超时了")

return

default:

fmt.Println("等待...")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

}

}

运行结果:

等待...

等待...

等待...

网络访问超时了

- select timeout 模式核心是通过 time.After 函数设置的超时时间,防止因为异常造成 select 语句无限等待

注意:

不要写成这样for { select { case v := <-result: fmt.Println(v) case <-time.After(3 * time.Second): //不要写在 select 里面 fmt.Println("网络访问超时了") return default: fmt.Println("等待...") time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) } }case <- time.After(time.Second) 是本次监听动作的超时时间,意思就说,只有在本次 select 操作中会有效,再次 select 又会重新开始计时,但是有default ,那case 超时操作,肯定执行不到了。

Context 的 WithTimeout 函数超时取消

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// 创建一个子节点的context,3秒后自动超时

//ctx, stop := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

ctx, stop := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 3*time.Second)

go func() {

worker(ctx, "打工人1")

}()

go func() {

worker(ctx, "打工人2")

}()

time.Sleep(5*time.Second) //工作5秒后休息

stop() //5秒后发出停止指令

fmt.Println("???")

}

func worker(ctx context.Context, name string){

for {

select {

case <- ctx.Done():

fmt.Println("下班咯~~~")

return

default:

fmt.Println(name, "认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...")

}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

}

运行结果:

打工人2 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

打工人1 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

打工人1 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

打工人2 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

打工人2 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

打工人1 认真摸鱼中,请勿打扰...

下班咯~~~

下班咯~~~

//两秒后

???

- 上面示例我们使用了 WithTimeout 函数超时取消,这是比较推荐的一种使用方式

Pipeline 模式

Pipeline 模式也成为流水线模式,模拟现实中的流水线生成。我们以组装手机为例,假设只有三道工序:零件采购、组装、打包成品:

零件采购(工序1)-》组装(工序2)-》打包(工序3)

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

coms := buy(10) //采购10套零件

phones := build(coms) //组装10部手机

packs := pack(phones) //打包它们以便售卖

//输出测试,看看效果

for p := range packs {

fmt.Println(p)

}

}

//工序1采购

func buy(n int) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for i := 1; i <= n; i++ {

out <- fmt.Sprint("零件", i)

}

}()

return out

}

//工序2组装

func build(in <-chan string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for c := range in {

out <- "组装(" + c + ")"

}

}()

return out

}

//工序3打包

func pack(in <-chan string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for c := range in {

out <- "打包(" + c + ")"

}

}()

return out

}

运行结果:

打包(组装(零件1))

打包(组装(零件2))

打包(组装(零件3))

打包(组装(零件4))

打包(组装(零件5))

打包(组装(零件6))

打包(组装(零件7))

打包(组装(零件8))

打包(组装(零件9))

打包(组装(零件10))

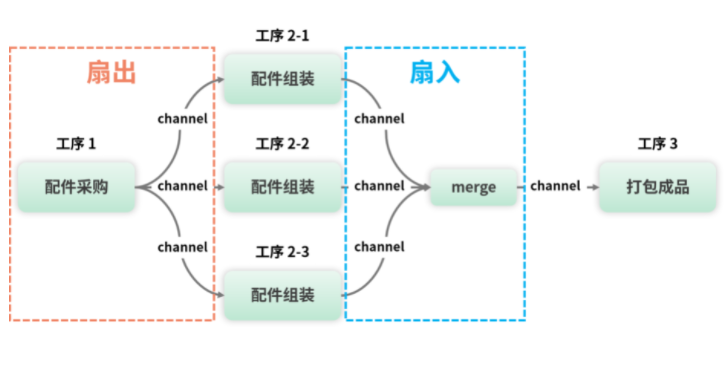

扇入扇出模式

手机流水线运转后,发现配件组装工序比较耗费时间,导致工序1和工序3也相应的慢了下来,为了提升性能,工序2增加了两班人手:

- 根据示意图能看到,红色部分为扇出,蓝色为扇入

改进后的流水线:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

coms := buy(10) //采购10套配件

//三班人同时组装100部手机

phones1 := build(coms)

phones2 := build(coms)

phones3 := build(coms)

//汇聚三个channel成一个

phones := merge(phones1,phones2,phones3)

packs := pack(phones) //打包它们以便售卖

//输出测试,看看效果

for p := range packs {

fmt.Println(p)

}

}

//工序1采购

func buy(n int) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for i := 1; i <= n; i++ {

out <- fmt.Sprint("零件", i)

}

}()

return out

}

//工序2组装

func build(in <-chan string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for c := range in {

out <- "组装(" + c + ")"

}

}()

return out

}

//工序3打包

func pack(in <-chan string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for c := range in {

out <- "打包(" + c + ")"

}

}()

return out

}

//扇入函数(组件),把多个chanel中的数据发送到一个channel中

func merge(ins ...<-chan string) <-chan string {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

out := make(chan string)

//把一个channel中的数据发送到out中

p:=func(in <-chan string) {

defer wg.Done()

for c := range in {

out <- c

}

}

wg.Add(len(ins))

//扇入,需要启动多个goroutine用于处于多个channel中的数据

for _,cs:=range ins{

go p(cs)

}

//等待所有输入的数据ins处理完,再关闭输出out

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(out)

}()

return out

}

运行结果:

打包(组装(零件2))

打包(组装(零件3))

打包(组装(零件1))

打包(组装(零件5))

打包(组装(零件7))

打包(组装(零件4))

打包(组装(零件6))

打包(组装(零件8))

打包(组装(零件9))

打包(组装(零件10))

- merge 和业务无关,不能当做一道工序,我们应该把它叫做 组件

- 组件是可以复用的,类似这种扇入工序,都可以使用 merge 组件

Futures 模式

Pipeline 流水线模式中的工序是相互依赖的,只有上一道工序完成,下一道工序才能开始。但是有的任务之间并不需要相互依赖,所以为了提高性能,这些独立的任务就可以并发执行。

Futures 模式可以理解为未来模式,主协程不用等待子协程返回的结果,可以先去做其他事情,等未来需要子协程结果的时候再来取,如果子协程还没有返回结果,就一直等待。

我们以火锅为例,洗菜、烧水这两个步骤之间没有依赖关系,可以同时做,最后

示例:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

vegetablesCh := washVegetables() //洗菜

waterCh := boilWater() //烧水

fmt.Println("已经安排好洗菜和烧水了,我先开一局")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("要做火锅了,看看菜和水好了吗")

vegetables := <-vegetablesCh

water := <-waterCh

fmt.Println("准备好了,可以做火锅了:",vegetables,water)

}

//洗菜

func washVegetables() <-chan string {

vegetables := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

vegetables <- "洗好的菜"

}()

return vegetables

}

//烧水

func boilWater() <-chan string {

water := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

water <- "烧开的水"

}()

return water

}

运行结果:

已经安排好洗菜和烧水了,我先开一局

要做火锅了,看看菜和水好了吗

准备好了,可以做火锅了: 洗好的菜 烧开的水

- Futures 模式下的协程和普通协程最大的区别是可以返回结果,而这个结果会在未来的某个时间点使用。所以在未来获取这个结果的操作必须是一个阻塞的操作,要一直等到获取结果为止。

- 如果你的大任务可以拆解为一个个独立并发执行的小任务,并且可以通过这些小任务的结果得出最终大任务的结果,就可以使用 Futures 模式。