As in Europe, a sword was the primary weapon of the feudal nobility. The katana was a single bladed longsword with a slight curve. The samurai wore them on their left hip. The best katana were the creations of master craftsmen with blades of incredible strength and sharpness. They were usually worn with the edge facing down.

Samurai Warrior on horseback, armed with a bow.

A shorter sword than the katana, the wakizashi was often paired with it, enabling the samurai to own a decorative set of swords. Together with the katana, it became the iconic weapon of the samurai.

The naginata, a long-bladed polearm, was a traditional weapon throughout the history of feudal Japan. It was especially popular with the sohei, a sect of warrior monks. It was also common among infantry and sometimes used by samurai, giving them extra reach.

No-Dachi

Being somewhere between a katana and a naginata in design, a no-dachi was an incredibly long sword, sometimes as tall as a man. It was wielded with two hands and carried across the back in a long scabbard.

Tanto

At the opposite end of the scale from the no-dachi was the tanto. Most samurai carried one of these short, sharp daggers. Some carried two.

The tanto was not a primary weapon of war. Given its length, it was of little use against swords and spears. It had a ceremonial and decorative function. It was also a weapon of last resort and was used in the suicides of many samurais who ended their lives after battlefield failures.

Samurai with sword, ca. 1860

Helmet

As in most conflicts, a helmet was one of the most important pieces of armor a samurai warrior could wear. Based on a metal bowl shape protecting the head, the first samurai helmets had wide fukigayeshi (turn backs beside the face) and shikoro (a neck guard). Over time, both shrank, although some form of shikoro remained. Late in the development of the samurai, men of high status added plumes, horns, or other decoration to their helmets.

Yoroi Armour

Early samurai wore a type of armor called yoroi. It was made by binding small armor scales together using leather thongs then lacquering the resulting plate. Thick silk cords were bound together overlapping yoroi plates. A samurai usually wore armor on the body, as a skirt over the upper legs, and as shoulder flaps that left the arms free for archery.

Agemaki

The agemaki was a knot of silk cords that bound yoroi armor together at the back. It became a decorative status symbol and was still worn on armor long after it was no longer needed to hold it together. It was displaced by the more visible sashimono banner.

Kote

A samurai who was not using a bow could wear armored sleeves called kote under his shoulder pads. Early on, these were cloth bags with metal plates sewn on. Later, as samurai gave up the bow and fought up close, other types of kote emerged, including chainmail.

Leg Armour

Like the kote, leg armor evolved in its protection. The suneate, (guards for the lower legs) became longer and were joined by the haidate, (thigh guards).

Haramaki Armour

The style of armor that replaced yoroi was haramaki. It fitted the wearer tightly and was in some ways more like the armor of regular infantry. Large shoulder guards were replaced with smaller, close-fitting ones.

Tatami-Gusoku

A later form of samurai armor, the tatami-gusoku was also one of the simplest. A selection of armor plates sewn onto a cloth backing, it was joined using chainmail links.

Hoate

The hoate was a face plate attached to a samurai’s helmet. It appeared relatively late in the development of samurai arms and armor.

In the early 16th century, the hoate was relatively small. It covered the chin and was an anchoring plate for cords holding a helmet in place.

By the end of the century, it had grown into a full face mask. Shaped into a snarling and intimidating visage, it showed a face even more fearsome than the samurai underneath. It often had a mustache of horse hair bristles.

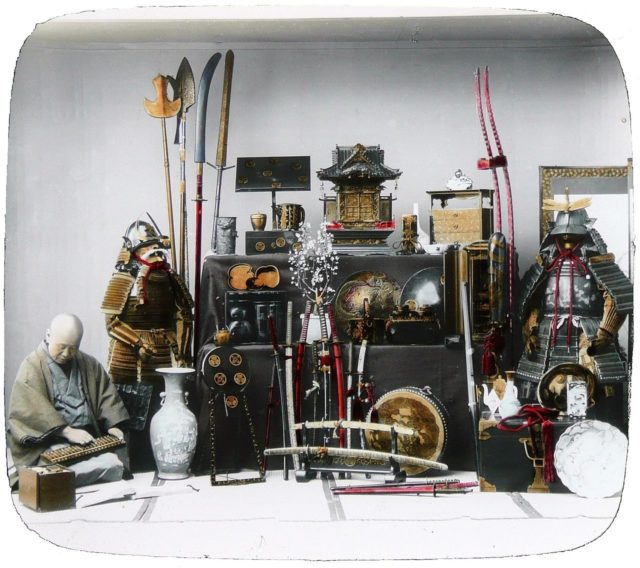

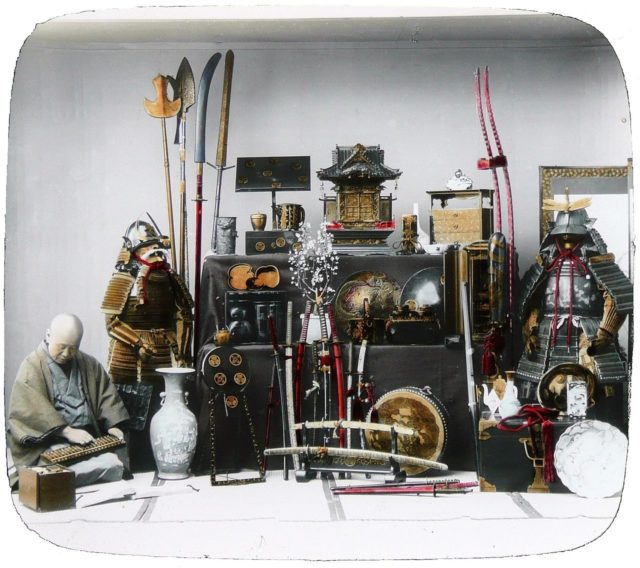

1890s photo showing a variety of armor and weapons typically used by samurai.

1890s photo showing a variety of armor and weapons typically used by samurai.

Signalling Fan

To pass messages and orders to their troops in battle, samurai carried signaling fans. They were small and decorative. Some styles were reserved only for commanders.

Referees still use them in sumo wrestling matches.

Sashimono

Another important part of signaling and organizing samurai in battle was the sashimono. It was a banner suspended on a pole and worn on the back of a samurai’s armor. It was emblazoned with the mon, or badge, of the commander the samurai served.

Like many heraldic displays, it served several functions in battle. It was a way of showing off a samurai’s presence and glorifying a commander who brought many men to fight. It was a way of intimidating the enemy, with row upon row of banners showing the presence of elite samurai warriors. It was also a way of telling who was on which side in the heat of a battle.

Wooden Shields

Samurai did not carry shields into battle, but still made use of them. Free-standing wooden boards, held up by poles extending from the back, were planted on the ground to provide cover for archers.

Source:

Stephen Turnbull (1987), Samurai Warriors

Samurai Warrior on horseback, armed with a bow.

Samurai Warrior on horseback, armed with a bow.

Samurai with sword, ca. 1860

Samurai with sword, ca. 1860 1890s photo showing a variety of armor and weapons typically used by samurai.

1890s photo showing a variety of armor and weapons typically used by samurai.