Chapter7

Extracting Information from Text 从文本提取信息

For any given question, it's likely that someone has written the answer down somewhere. The amount of natural language text that is available in electronic form is truly staggering(令人惊愕的), and is increasing every day. However, the complexity of natural language can make it very difficult to access the information in that text. The state of the art(目前的技术水平) in NLP is still a long way from being able to build general-purpose(多种目的) representations of meaning from unrestricted text. If we instead focus our efforts on a limited set of questions or "entity relations," such as "where are different facilities located," or "who is employed by what company," we can make significant progress. The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

1. How can we build a system that extracts structured data, such as tables, from unstructured text?

我们如何构建一个系统从非结构化的文本中来抽取结构化数据,例如表

2. What are some robust methods for identifying the entities and relationships described in a text?

有哪些强健的方法来识别文中描述的实体和关系?

3. Which corpora are appropriate for this work, and how do we use them for training and evaluating our models?

哪个语料库适合这项工作,并且我们如何使用它们来训练和评价我们的 模型?

Along the way, we'll apply techniques from the last two chapters to the problems of chunking and named-entity recognition.

沿着这种方式,我们将应用最后两章中的技术来解决分块和命名实体识别。

7.1 Information Extraction 信息抽取

Information comes in many shapes and sizes. One important form is structured data(结构化数据), where there is a regular and predictable organization of entities and relationships. For example, we might be interested in the relation between companies and locations. Given a particular company, we would like to be able to identify the locations where it does business; conversely, given a location, we would like to discover which companies do business in that location. If our data is in tabular form, such as the example in Table 7.1, then answering these queries is straightforward.

| OrgName | LocationName |

| Omnicom | New York |

| DDB Needham | New York |

| Kaplan Thaler Group | New York |

| BBDO South | Atlanta |

| Georgia-Pacific | Atlanta |

If this location data was stored in Python as a list of tuples (entity, relation, entity), then the question "Which organizations operate in Atlanta?" could be translated as follows:

|

Things are more tricky(棘手的) if we try to get similar information out of text. For example, consider the following snippet (from nltk.corpus.ieer, for fileid NYT19980315.0085).

| (1) | The fourth Wells account moving to another agency is the packaged paper-products division of Georgia-Pacific Corp., which arrived at Wells only last fall. Like Hertz and the History Channel, it is also leaving for an Omnicom-owned agency, the BBDO South unit of BBDO Worldwide. BBDO South in Atlanta, which handles corporate advertising for Georgia-Pacific, will assume additional duties for brands like Angel Soft toilet tissue and Sparkle paper towels, said Ken Haldin, a spokesman for Georgia-Pacific in Atlanta. |

If you read through (1), you will glean(收集) the information required to answer the example question. But how do we get a machine to understand enough about (1) to return the answers in Table 7.2? This is obviously a much harder task. Unlike Table 7.1, (1) contains no structure that links organization names with location names.

One approach to this problem involves building a very general representation of meaning (Chapter 10). In this chapter we take a different approach, deciding in advance that we will only look for very specific kinds of information in text, such as the relation between organizations and locations. Rather than trying to use text like (1) to answer the question directly, we first convert the unstructured data of natural language sentences into the structured data of Table 7.1. Then we reap the benefits of (获得益处)powerful query tools such as SQL. This method of getting meaning from text is called Information Extraction(信息提取).

Information Extraction has many applications, including business intelligence, resume harvesting, media analysis, sentiment detection(情感检测), patent search(专利检索), and email scanning. A particularly important area of current research involves the attempt to extract structured data out of electronically-available scientific literature, especially in the domain of biology and medicine.

Information Extraction Architecture 信息提取结构

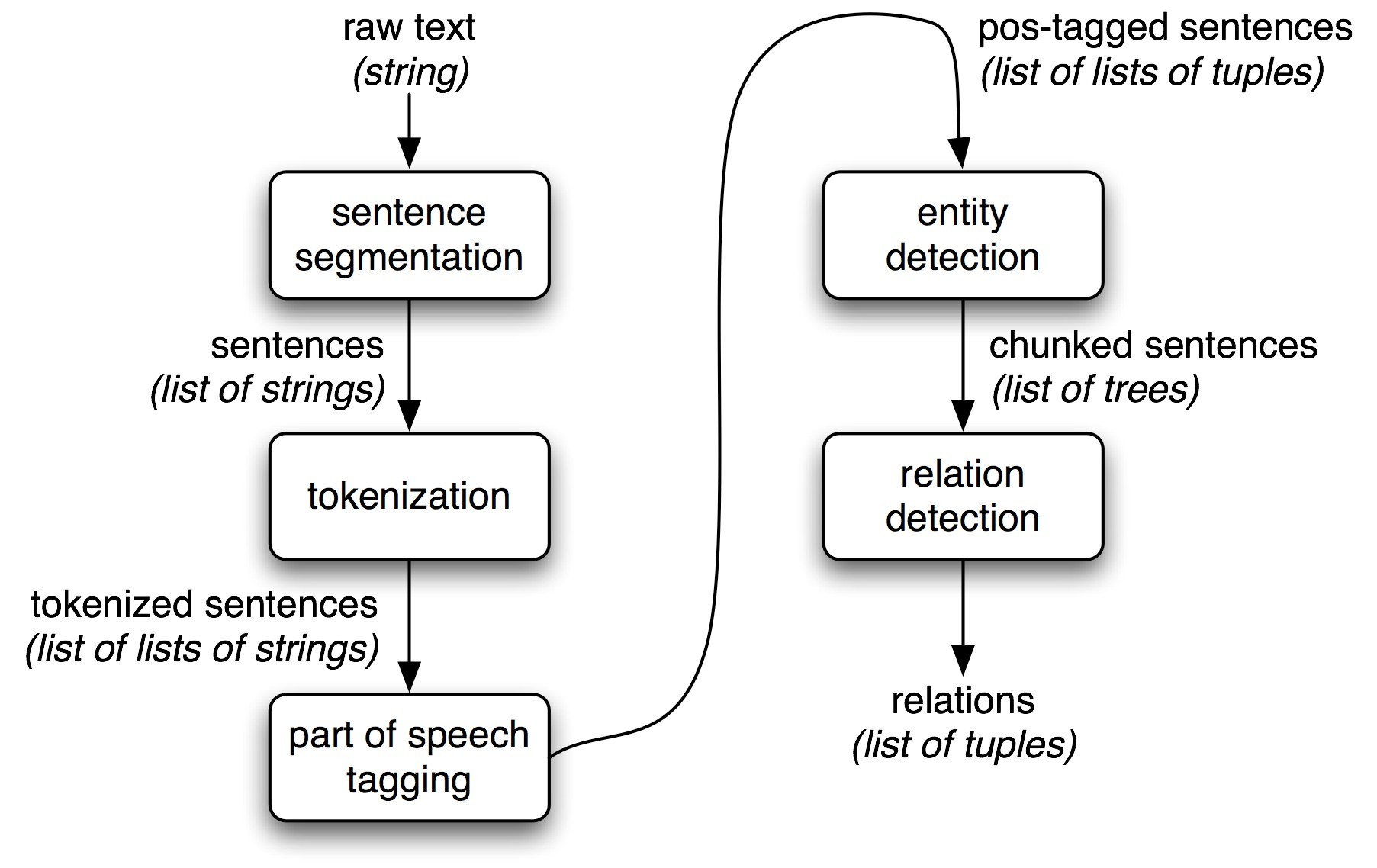

Figure 7.1 shows the architecture for a simple information extraction system. It begins by processing a document using several of the procedures discussed in Chapter 3 and Chapter 5: first, the raw text of the document is split into sentences using a sentence segmenter, and each sentence is further subdivided into words using a tokenizer. Next, each sentence is tagged with part-of-speech tags, which will prove very helpful in the next step, named entity detection(命名实体检测). In this step, we search for mentions of(提及) potentially interesting entities in each sentence. Finally, we use relation detection(关系检测) to search for likely relations between different entities in the text.

Figure 7.1: Simple Pipeline Architecture for an Information Extraction System. This system takes the raw text of a document as its input, and generates a list of (entity, relation, entity) tuples as its output. For example, given a document that indicates that the company Georgia-Pacific is located in Atlanta, it might generate the tuple ([ORG: 'Georgia-Pacific'] 'in' [LOC: 'Atlanta']).

To perform the first three tasks, we can define a simple function that simply connects together NLTK's default sentence segmenter, word tokenizer, and part-of-speech tagger:

|

Next, in named entity detection, we segment and label the entities that might participate in interesting relations with one another. Typically, these will be definite noun phrases such as the knights who say "ni", or proper names such as Monty Python. In some tasks it is useful to also consider indefinite(不明确的) nouns or noun chunks, such as every student or cats, and these do not necessarily refer to entities in the same way as definite NPs and proper names.

Finally, in relation extraction, we search for specific patterns between pairs of entities that occur near one another in the text, and use those patterns to build tuples recording the relationships between the entities.