So you have some data that you want to store in a file or send over the network. You may find yourself going through several phases of evolution:

- Using your programming language’s built-in serialization, such as Java serialization, Ruby’s marshal, or Python’s pickle. Or maybe you even invent your own format.

- Then you realise that being locked into one programming language sucks, so you move to using a widely supported, language-agnostic format like JSON (or XML if you like to party like it’s 1999).

- Then you decide that JSON is too verbose and too slow to parse, you’re annoyed that it doesn’t differentiate integers from floating point, and think that you’d quite like binary strings as well as Unicode strings. So you invent some sort of binary format that’s kinda like JSON, but binary (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

- Then you find that people are stuffing all sorts of random fields into their objects, using inconsistent types, and you’d quite like a schema and somedocumentation, thank you very much. Perhaps you’re also using a statically typed programming language and want to generate model classes from a schema. Also you realize that your binary JSON-lookalike actually isn’t all that compact, because you’re still storing field names over and over again; hey, if you had a schema, you could avoid storing objects’ field names, and you could save some more bytes!

Once you get to the fourth stage, your options are typically Thrift, Protocol Buffers orAvro. All three provide efficient, cross-language serialization of data using a schema, and code generation for the Java folks.

Plenty of comparisons have been written about them already (1, 2, 3, 4). However, many posts overlook a detail that seems mundane at first, but is actually cruicial: What happens if the schema changes?

In real life, data is always in flux. The moment you think you have finalised a schema, someone will come up with a use case that wasn’t anticipated, and wants to “just quickly add a field”. Fortunately Thrift, Protobuf and Avro all support schema evolution: you can change the schema, you can have producers and consumers with different versions of the schema at the same time, and it all continues to work. That is an extremely valuable feature when you’re dealing with a big production system, because it allows you to update different components of the system independently, at different times, without worrying about compatibility.

Which brings us to the topic of today’s post. I would like to explore how Protocol Buffers, Avro and Thrift actually encode data into bytes — and this will also help explain how each of them deals with schema changes. The design choices made by each of the frameworks are interesting, and by comparing them I think you can become a better engineer (by a little bit).

The example I will use is a little object describing a person. In JSON I would write it like this:

{

"userName": "Martin",

"favouriteNumber": 1337,

"interests": ["daydreaming", "hacking"]

}This JSON encoding can be our baseline. If I remove all the whitespace it consumes 82 bytes.

Protocol Buffers

The Protocol Buffers schema for the person object might look something like this:

message Person {

required string user_name = 1;

optional int64 favourite_number = 2;

repeated string interests = 3;

}

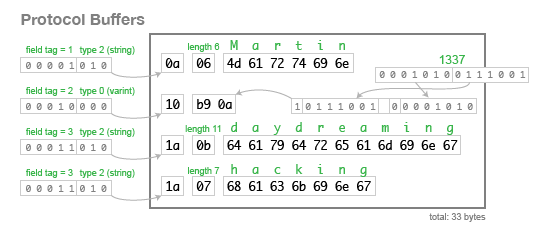

When we encode the data above using this schema, it uses 33 bytes, as follows:

Look exactly at how the binary representation is structured, byte by byte. The person record is just the concatentation of its fields. Each field starts with a byte that indicates its tag number (the numbers 1, 2, 3 in the schema above), and the type of the field. If the first byte of a field indicates that the field is a string, it is followed by the number of bytes in the string, and then the UTF-8 encoding of the string. If the first byte indicates that the field is an integer, a variable-length encoding of the number follows. There is no array type, but a tag number can appear multiple times to represent a multi-valued field.

This encoding has consequences for schema evolution:

- There is no difference in the encoding between

optional,requiredandrepeatedfields (except for the number of times the tag number can appear). This means that you can change a field fromoptionaltorepeatedand vice versa (if the parser is expecting anoptionalfield but sees the same tag number multiple times in one record, it discards all but the last value).requiredhas an additional validation check, so if you change it, you risk runtime errors (if the sender of a message thinks that it’s optional, but the recipient thinks that it’s required). - An

optionalfield without a value, or arepeatedfield with zero values, does not appear in the encoded data at all — the field with that tag number is simply absent. Thus, it is safe to remove that kind of field from the schema. However, you must never reuse the tag number for another field in future, because you may still have data stored that uses that tag for the field you deleted. - You can add a field to your record, as long as it is given a new tag number. If the Protobuf parser parser sees a tag number that is not defined in its version of the schema, it has no way of knowing what that field is called. But it does roughly know what type it is, because a 3-bit type code is included in the first byte of the field. This means that even though the parser can’t exactly interpret the field, it can figure out how many bytes it needs to skip in order to find the next field in the record.

- You can rename fields, because field names don’t exist in the binary serialization, but you can never change a tag number.

This approach of using a tag number to represent each field is simple and effective. But as we’ll see in a minute, it’s not the only way of doing things.

Avro

Avro schemas can be written in two ways, either in a JSON format:

{

"type": "record",

"name": "Person",

"fields": [

{"name": "userName", "type": "string"},

{"name": "favouriteNumber", "type": ["null", "long"]},

{"name": "interests", "type": {"type": "array", "items": "string"}}

]

}…or in an IDL:

record Person {

string userName;

union { null, long } favouriteNumber;

array<string> interests;

}

Notice that there are no tag numbers in the schema! So how does it work?

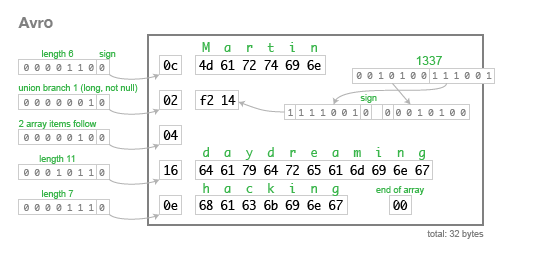

Here is the same example data encoded in just 32 bytes:

Strings are just a length prefix followed by UTF-8 bytes, but there’s nothing in the bytestream that tells you that it is a string. It could just as well be a variable-length integer, or something else entirely. The only way you can parse this binary data is by reading it alongside the schema, and the schema tells you what type to expect next. You need to have the exact same version of the schema as the writer of the data used. If you have the wrong schema, the parser will not be able to make head or tail of the binary data.

So how does Avro support schema evolution? Well, although you need to know the exact schema with which the data was written (the writer’s schema), that doesn’t have to be the same as the schema the consumer is expecting (the reader’s schema). You can actually give two different schemas to the Avro parser, and it uses resolution rulesto translate data from the writer schema into the reader schema.

This has some interesting consequences for schema evolution:

- The Avro encoding doesn’t have an indicator to say which field is next; it just encodes one field after another, in the order they appear in the schema. Since there is no way for the parser to know that a field has been skipped, there is no such thing as an optional field in Avro. Instead, if you want to be able to leave out a value, you can use a union type, like

union { null, long }above. This is encoded as a byte to tell the parser which of the possible union types to use, followed by the value itself. By making a union with thenulltype (which is simply encoded as zero bytes) you can make a field optional. - Union types are powerful, but you must take care when changing them. If you want to add a type to a union, you first need to update all readers with the new schema, so that they know what to expect. Only once all readers are updated, the writers may start putting this new type in the records they generate.

- You can reorder fields in a record however you like. Although the fields are encoded in the order they are declared, the parser matches fields in the reader and writer schema by name, which is why no tag numbers are needed in Avro.

- Because fields are matched by name, changing the name of a field is tricky. You need to first update all readers of the data to use the new field name, while keeping the old name as an alias (since the name matching uses aliases from the reader’s schema). Then you can update the writer’s schema to use the new field name.

- You can add a field to a record, provided that you also give it a default value (e.g.

nullif the field’s type is a union withnull). The default is necessary so that when a reader using the new schema parses a record written with the old schema (and hence lacking the field), it can fill in the default instead. - Conversely, you can remove a field from a record, provided that it previously had a default value. (This is a good reason to give all your fields default values if possible.) This is so that when a reader using the old schema parses a record written with the new schema, it can fall back to the default.

This leaves us with the problem of knowing the exact schema with which a given record was written. The best solution depends on the context in which your data is being used:

- In Hadoop you typically have large files containing millions of records, all encoded with the same schema. Object container files handle this case: they just include the schema once at the beginning of the file, and the rest of the file can be decoded with that schema.

- In an RPC context, it’s probably too much overhead to send the schema with every request and response. But if your RPC framework uses long-lived connections, it can negotiate the schema once at the start of the connection, and amortize that overhead over many requests.

- If you’re storing records in a database one-by-one, you may end up with different schema versions written at different times, and so you have to annotate each record with its schema version. If storing the schema itself is too much overhead, you can use a hash of the schema, or a sequential schema version number. You then need a schema registry where you can look up the exact schema definition for a given version number.

One way of looking at it: in Protocol Buffers, every field in a record is tagged, whereas in Avro, the entire record, file or network connection is tagged with a schema version.

At first glance it may seem that Avro’s approach suffers from greater complexity, because you need to go to the additional effort of distributing schemas. However, I am beginning to think that Avro’s approach also has some distinct advantages:

- Object container files are wonderfully self-describing: the writer schema embedded in the file contains all the field names and types, and even documentation strings (if the author of the schema bothered to write some). This means you can load these files directly into interactive tools like Pig, and it Just Works™ without any configuration.

- As Avro schemas are JSON, you can add your own metadata to them, e.g. describing application-level semantics for a field. And as you distribute schemas, that metadata automatically gets distributed too.

- A schema registry is probably a good thing in any case, serving as documentationand helping you to find and reuse data. And because you simply can’t parse Avro data without the schema, the schema registry is guaranteed to be up-to-date. Of course you can set up a protobuf schema registry too, but since it’s not requiredfor operation, it’ll end up being on a best-effort basis.

Thrift

Thrift is a much bigger project than Avro or Protocol Buffers, as it’s not just a data serialization library, but also an entire RPC framework. It also has a somewhat different culture: whereas Avro and Protobuf standardize a single binary encoding, Thriftembraces a whole variety of different serialization formats (which it calls “protocols”).

Indeed, Thrift has two different JSON encodings, and no fewer than three different binary encodings. (However, one of the binary encodings, DenseProtocol, is only supported in the C++ implementation; since we’re interested in cross-language serialization, I will focus on the other two.)

All the encodings share the same schema definition, in Thrift IDL:

struct Person {

1: string userName,

2: optional i64 favouriteNumber,

3: list<string> interests

}

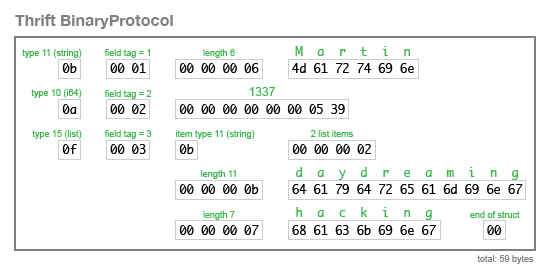

The BinaryProtocol encoding is very straightforward, but also fairly wasteful (it takes 59 bytes to encode our example record):

The CompactProtocol encoding is semantically equivalent, but uses variable-length integers and bit packing to reduce the size to 34 bytes:

As you can see, Thrift’s approach to schema evolution is the same as Protobuf’s: each field is manually assigned a tag in the IDL, and the tags and field types are stored in the binary encoding, which enables the parser to skip unknown fields. Thrift defines an explicit list type rather than Protobuf’s repeated field approach, but otherwise the two are very similar.

In terms of philosophy, the libraries are very different though. Thrift favours the “one-stop shop” style that gives you an entire integrated RPC framework and many choices (with varying cross-language support), whereas Protocol Buffers and Avro appear to follow much more of a “do one thing and do it well” style.