In one embodiment, a method includes transitioning control to a virtual machine (VM) from a virtual machine monitor (VMM), determining that a VMM timer indicator is set to an enabling value, and identifying a VMM timer value configured by the VMM. The method further includes periodically comparing a current value of a timing source with the VMM timer value, generating an internal event if the current value of the timing source has reached the VMM timer value, and transitioning control to the VMM in response to the internal event without incurring an event handling procedure in any one of the VMM and the VM.

FIELD

Embodiments of the invention relate generally to virtual machines, and more specifically to providing support for a timer associated with a virtual machine monitor.

BACKGROUND

Timers and time reference sources are typically used by operating systems and application software to schedule and optimize activities. For example, an operating system kernel may use a timer to allow a plurality of user-level applications to time-share the resources of the system (e.g., the central processing unit (CPU)). An example of a timer used on a personal computer (PC) platform is the 8254 Programmable Interval Timer. This timer may be configured to issue interrupts after a specified interval or periodically.

An example of a time reference source is the timestamp counter (TSC) used in the instruction set architecture (ISA) of the Intel® Pentium® 4 (referred to herein as the IA-32 ISA). The TSC is a 64-bit counter that is set to 0 following the hardware reset of the processor, and then incremented every processor clock cycle, even when the processor is halted by the HLT instruction. The TSC cannot be used to generate interrupts. It is a time reference only, useful to measure time intervals. The IA-32 ISA provides an instruction (RDTSC) to read the value of the TSC and an instruction (WRMSR) to write the TSC. When WRMSR is used to write the timestamp counter, only the 32 low-order bits may be written; the 32 high-order bits are cleared to 0.

In a virtual machine system, a virtual-machine monitor (VMM) may need to utilize platform-based timers in a manner similar to that of a conventional operating system. For example, a VMM may use timers to schedule resources, assure security, provide quality of service, etc.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE DRAWINGS

The present invention is illustrated by way of example, and not by way of limitation, in the figures of the accompanying drawings and in which like reference numerals refer to similar elements and in which:

FIG. 1 illustrates one embodiment of a virtual-machine environment, in which the present invention may operate;

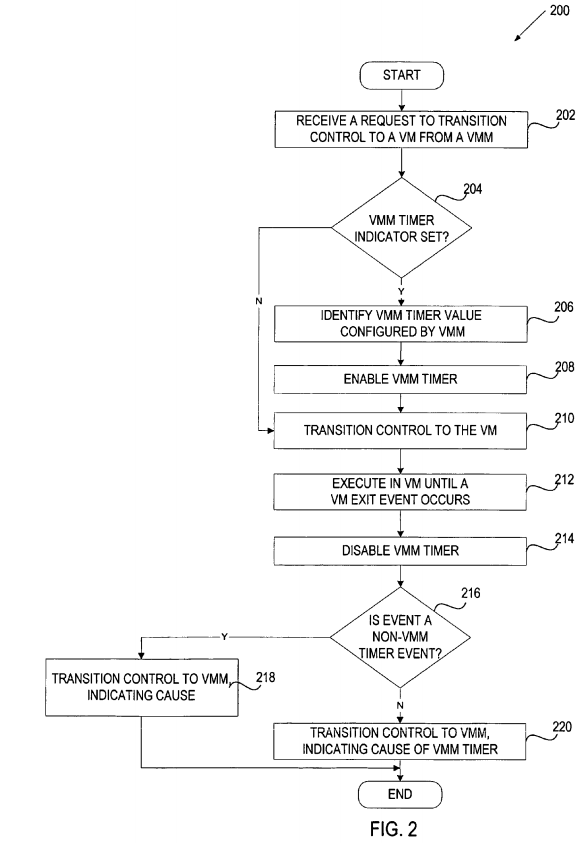

FIG. 2 is a flow diagram of one embodiment of a process for providing support for a timer associated with a VMM;

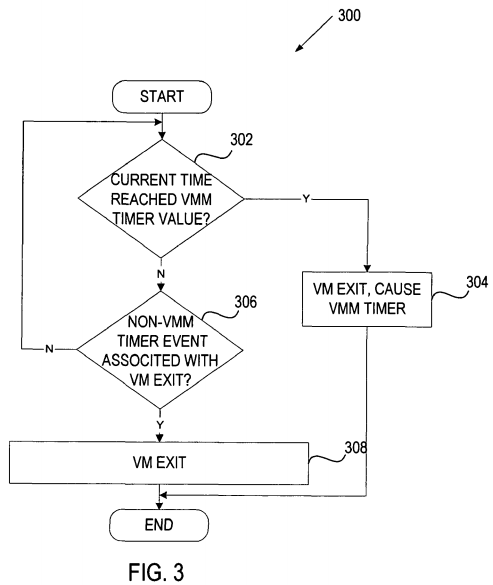

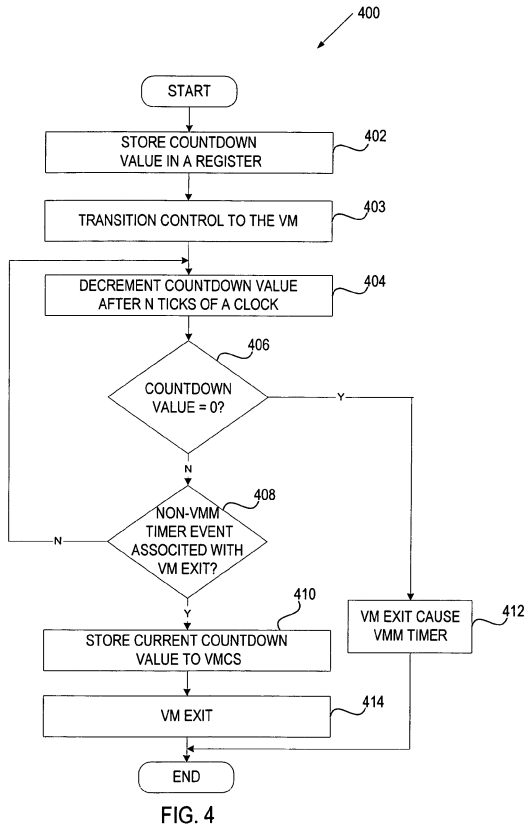

FIGS. 3 and 4 are flow diagrams of two embodiment of a process for utilizing a VMM timer to decide whether to return control to a VMM; and

FIG. 5 is a flow diagram of one embodiment of a process for configuring a timer associated with a VMM.

DESCRIPTION OF EMBODIMENTS

A method and apparatus for providing support for a timer associated with a virtual machine monitor is described. In the following description, for purposes of explanation, numerous specific details are set forth in order to provide a thorough understanding of the present invention. It will be apparent, however, to one skilled in the art that the present invention can be practiced without these specific details.

FIG. 1 illustrates one embodiment of a virtual-machine environment 100, in which the present invention may operate. In this embodiment, bare platform hardware116 comprises a computing platform, which may be capable, for example, of executing a standard operating system (OS) or a virtual-machine monitor (VMM), such as a VMM 112.

The VMM 112, though typically implemented in software, may emulate and export a bare machine interface to higher level software. Such higher level software may comprise a standard or real-time OS, may be a highly stripped down operating environment with limited operating system functionality, may not include traditional OS facilities, etc. Alternatively, for example, the VMM 112 may be run within, or on top of, another VMM. VMMs may be implemented, for example, in hardware, software, firmware or by a combination of various techniques.

The platform hardware 116 can be of a personal computer (PC), mainframe, handheld device, portable computer, set-top box, or any other computing system. The platform hardware 116 includes a processor 118 and memory 120.

Processor 118 can be any type of processor capable of executing software, such as a microprocessor, digital signal processor, microcontroller, or the like. The processor 118 may include microcode, programmable logic or hardcoded logic for performing the execution of method embodiments of the present invention. Although FIG. 1 shows only one such processor 118, there may be one or more processors in the system.

Memory 120 can be a hard disk, a floppy disk, random access memory (RAM), read only memory (ROM), flash memory, any combination of the above devices, or any other type of machine medium readable by processor 118. Memory 120may store instructions and/or data for performing the execution of method embodiments of the present invention.

The VMM 112 presents to other software (i.e., "guest" software) the abstraction of one or more virtual machines (VMs), which may provide the same or different abstractions to the various guests. FIG. 1 shows two VMs, 102 and 114. The guest software running on each VM may include a guest OS such as a guest OS104 or 106 and various guest software applications 108 and 110. Each of the guest OSs 104 and 106 expects to access physical resources (e.g., processor registers, memory and I/O devices) within the VMs 102 and 114 on which the guest OS 104 or 106 is running and to perform other functions. For example, the guest OS 104 or 106 expects to have access to all registers, caches, structures, I/O devices, memory and the like, according to the architecture of the processor and platform presented in the VM 102 and 114. The resources that can be accessed by the guest software may either be classified as "privileged" or "non-privileged." For privileged resources, the VMM 112 facilitates functionality desired by guest software while retaining ultimate control over these privileged resources. Non-privileged resources do not need to be controlled by the VMM112 and can be accessed by guest software.

Further, each guest OS expects to handle various fault events such as exceptions (e.g., page faults, general protection faults, etc.), interrupts (e.g., hardware interrupts, software interrupts), and platform events (e.g., initialization (NIT) and system management interrupts (SMIs)). Some of these fault events are "privileged" because they must be handled by the VMM 112 to ensure proper operation of VMs 102 and 114 and for protection from and among guest software.

When a privileged fault event occurs or guest software attempts to access a privileged resource, control may be transferred to the VMM 112. The transfer of control from guest software to the VMM 112 is referred to herein as a VM exit. After facilitating the resource access or handling the event appropriately, the VMM 112 may return control to guest software. The transfer of control from the VMM 112 to guest software is referred to as a VM entry.

In one embodiment, the processor 118 controls the operation of the VMs 102 and 114 in accordance with data stored in a virtual machine control structure (VMCS) 124. The VMCS 124 is a structure that may contain the state of guest software, the state of the VMM 112, execution control information indicating how the VMM 112 wishes to control operation of guest software, information controlling transitions between the VMM 112 and a VM, etc. The processor 118 reads information from the VMCS 124 to determine the execution environment of the VM and to constrain its behavior. In one embodiment, the VMCS is stored in memory 120. In some embodiments, multiple VMCS structures are used to support multiple VMs.

In one embodiment, when a VM exit occurs, components of the processor state used by guest software are saved, components of the processor state required by the VMM 112 are loaded, and the execution resumes in the VMM 112. In one embodiment, the components of the processor state used by guest software are stored in a guest-state area of VMCS124 and the components of the processor state required by the VMM 112 are stored in a monitor-state area of VMCS 124. In one embodiment, when a transition from the VMM 112 to guest software occurs, the processor state that was saved at the VM exit (and may have been modified by the VMM 112 while processing the VM exit) is restored and control is returned to the VM 102 or 114.

An event causing a VM exit may or may not require the execution of an "event handling" procedure. The event handling procedure refers to event reporting that changes control flow of the code executing on the processor even though no branches requiring such a change exist in the code. Event reporting is typically performed when an event is an exception or an interrupt and may require saving the state of the running code (e.g., on a stack), locating an interrupt vector by traversing a redirection structure (e.g., the interrupt descriptor table (IDT) in the instruction set architecture (ISA) of the Intel® Pentium® 4 (referred to herein as the IA-32 ISA)), loading the state of the event handler, and starting execution in the new code. When an exception or interrupt occurs during the operation of the VM 102 or 114, and this exception or interrupt should be handled by the VMM 112 (e.g., an I/O completion interrupt for an I/O operation that was not initiated by or on behalf of the running VM 102 or 114), the event handling procedure is executed after exiting the running VM 102 or 114 (i.e., transitioning control to the VMM 112).

Some events do not require the above-referenced event handling procedure to be executed in either the VMM 112 or the VM 102 or 114. Such events are referred to herein as internal events. For example, the VM 102 or 114 may incur a page fault on a page, which the VMM 112 has paged out but the VM 102 or 114 expects to be resident. Such a page fault cannot cause the event handling procedure, in order to prevent a violation of virtualization. Instead, this page fault is handled using a VM exit, which causes the VM state to be saved in the VMCS 124, with the execution resuming in the VMM 112, which handles the page fault and transitions control back to the VM 102 or 114.

The VMM 112 may need to gain control during the operation of the VM 102 or 114 to schedule resources, provide quality of service, assure security, and perform other functions. Hence, the VMM 112 needs to have a timer mechanism allowing the VMM 112 to indicate the desired time for gaining control. In one embodiment, the VMM 112 includes a timer configuration module 126 that provides values for fields associated with the VMM timer prior to requesting a transition of control to the VM 102 or 114. These fields may include, for example, a VMM timer indicator specifying whether a VMM timer should be enabled, and a VMM timer value field indicating a desired time for regaining control.

In one embodiment, the VMM timer indicator and the VMM timer value are stored in the VMCS 124. Alternatively, the VMM timer indicator and the VMM timer value may reside in the processor 118, a combination of the memory 120 and the processor 118, or in any other storage location or locations. In one embodiment, a separate pair of the VMM timer indicator and VMM timer value is maintained for each of the VMs 102 and 114. Alternatively, the same VMM timer indicator and VMM timer value are maintained for both VMs 102 and 144 and are updated by the VMM 112 before each VM entry.

In one embodiment, in which the system 100 includes multiple processors or multi-threaded processors, each of the logical processors is associated with a separate pair of the VMM timer indicator and VMM timer value, and the VMM 112configures the VMM timer indicator and VMM timer value for each of the logical processors.

In one embodiment, the processor 118 includes VMM timer support logic 122 that is responsible for determining whether the VMM timer is enabled based on the VMM timer indicator. If the VMM timer is enabled, the VMM timer support logic 122decides when to transition control to the VMM 112 using the VMM timer value specified by the VMM 112.

In one embodiment, the VMM timer value specifies the time at which control should be returned to the VMM 112. During the operation of the VM 102 or 114, the VMM timer support logic 122 periodically (e.g., after each cycle executed by the currently operating VM 102 or 114) compares the current value of the timing source with the VMM timer value specified by the VMM 112. The timing source may be any clock used by the system 100 to measure time intervals. For example, in the IA-32 ISA, the timing source used for measuring time intervals may be the timestamp counter (TSC).

When the current time provided by the timing source "reaches" the VMM timer value specified by the VMM 112, the VMM timer support logic 122 transitions control to the VMM 112, indicating that the cause of the transition is the VMM timer. The current time "reaches" the VMM timer value if the current time matches the VMM timer value or exceeds the timer value (when an exact match between the current time and the VMM timer value is not possible).

In another embodiment, the VMM timer value specifies the time interval at the end of which the VMM 112 should gain control. During the operation of the VM 102 or 114, the VMM timer support logic 122 uses this time interval as a countdown value, periodically decrementing it (e.g., every N ticks of the clock). When the countdown value reaches zero, the VMM timer support logic 122 transitions control to the VMM 112. In one embodiment, if a VM exit occurs prior to the expiration of the countdown value (e.g. due to a fault detected during the operation of the VM), the VMM timer support logic 122 stores a current countdown value to the VMCS 124. The stored countdown value may replace the VMM timer value previously specified by the VMM 112 or be maintained in a designated countdown value field.

FIG. 2 is a flow diagram of one embodiment of a process 200 for providing support for a timer associated with a VMM. The process may be performed by processing logic that may comprise hardware (e.g., circuitry, dedicated logic, programmable logic, microcode, etc.), software (such as that run on a general purpose computer system or a dedicated machine), or a combination of both. In one embodiment, process 200 is performed by VMM timer support logic 122 of FIG. 1.

Referring to FIG. 2, process 200 begins with processing logic receiving a request to transition control to a VM from a VMM (i.e., the request for VM entry) (processing block 202). In one embodiment, the VM entry request is received via a VM entry instruction executed by the VMM.

Next, processing logic determines whether a VMM timer indicator is set to an enabling value (processing box 204). The VMM timer indicator is configured by the VMM and may be set to the enabling value to indicate that the VMM timer mechanism is enabled. As discussed above, the VMM timer mechanism (also referred to herein as the VMM timer) allows the VMM to gain control at a specific point of time during the operation of the VM.

If the determination made at processing box 204 is negative (the VMM timer indicator is set to a disabling value), processing logic proceeds to processing box 210.

If the determination made at processing box 204 is positive, processing logic identifies a VMM timer value configured by the VMM (processing block 206). In one embodiment, processing logic identifies the VMM timer value by retrieving it from the VMCS. The VMM stores the VMM timer value to the VMCS prior to issuing a VM entry request. At processing block 208, processing logic configures and enables the VMM timer using the VMM timer value.

In one embodiment, the VMM timer value specifies the time at which control should be returned to the VMM. The VMM may calculate this timer value by adding an offset value (i.e., a time interval specifying how long the VM is allowed to execute) to the value of the timing source read by the VMM at the time of calculation. In another embodiment, the VMM timer value is an offset time interval specifying how long the VM is allowed to execute.

Next, processing logic transitions control to the VM (processing block 210) and allows the VM to execute until an event associated with a VM exit occurs (processing block 212). In one embodiment, an event is associated with a VM exit if an execution control indicator associated with this event is set to a VM exit value to cause a VM exit for this event.

At processing block 214, the VMM timer is disabled. Note that if the VMM timer was not enabled in processing box 208, this processing step is not required. Next, if the event is a non-VMM timer event (e.g., a fault) associated with a VM exit (processing block 216), processing logic returns control to the VMM, indicating the cause of the VM exit (processing block218).

Alternatively, if the event is caused by the VMM timer (processing block 216), processing logic transitions control to the VMM, indicating that the VM exist was caused by the VMM timer (processing block 220).

The VMM timer will generate events to trigger a VM exit based on the VMM timer value specified by the VMM. In one embodiment, in which the VMM timer value specifies the time at which the VMM desires to gain control, processing logic makes the above decision by periodically comparing the current time of the clock (e.g., the TSC, or some other timing reference) with the VMM timer value until detecting that the clock reaches the VMM timer value. In another embodiment, in which the VMM timer value is an offset time value specifying how long the VM is allowed to execute, processing logic makes the above decision by periodically decrementing the offset time value until detecting that the offset time value reaches 0.

It should be noted that FIG. 2 illustrates an embodiment in which VM exits caused by non-VMM timer events may have higher priority than VM exits caused by the VMM timer. However, this prioritization may be different depending on a prioritization scheme being used, and, therefore, a decision pertaining to a VM exit caused by a non-VMM timer event can be made after a decision pertaining to a VM exit caused by the VMM timer (processing block 214). Additionally, some non-VMM timer events may have higher priority while other non-VMM timer events may have lower priority than the VMM timer event.

FIGS. 3 and 4 are flow diagrams of two embodiment of a process for utilizing a VMM timer to decide whether to return control to a VMM. The process may be performed by processing logic that may comprise hardware (e.g., circuitry, dedicated logic, programmable logic, microcode, etc.), software (such as that run on a general purpose computer system or a dedicated machine), or a combination of both. In one embodiment, the process is performed by VMM timer support logic 122 of FIG. 1.

Referring to FIG. 3, process 300 uses a VMM timer value that specifies the time at which control should be returned to the VMM. As discussed above, the VMM may calculate this timer value by adding an offset value (i.e., a time interval specifying how long the VM is allowed to execute) to the value of the timing source read by the VMM at the time of calculation.

Process 300 begins subsequent to determining that the VMM timer is enabled, identifying a VMM timer value configured by the VMM, and transitioning control to the VM, as illustrated in FIG. 2.

Initially, processing logic determines, during the operation of the VM, whether the current time provided by the timing source has reached the VMM timer value (processing box 302). As discussed above, the timing source may be any clock used by the system 100 to measure time intervals. For example, a processor supporting the IA-32 ISA may use the TSC to measure time intervals.

In an embodiment, not all of the bits in the timing source may be compared to the VMM timer value. Instead, only the high-order bits may be compared. The number of the bits compared is referred to as the VMM-timer-comparator length. In an embodiment, the VMM may determine the VMM-timer-comparator length by reading a capability model specific register (MSR) using the RDMSR instruction. In one embodiment, in which the TSC is used as the timing source, the determination of processing block 302 is made by comparing the high-order bits of the TSC with the same high-order bits of the VMM timer value, and if the TSC value is greater than or equal to the VMM timer value, then the comparison in processing block302 is satisfied.

If the current time of the timing source reaches the VMM timer value, processing logic creates an internal event and generates a VM exit, indicating that the cause of the VM exit is due to the VMM timer (processing block 304). As discussed above, because the VM exit is caused by an internal event, the execution will resume in the VMM without performing the event handling procedure that is typically performed for interrupts or exceptions after exiting the VM.

If the current time of the timing source has not yet reached the VMM timer value, processing logic checks for a non-VMM timer event associated with a VM exit (processing box 306). If such event occurs, processing logic generates a VM exit and indicates the source of the VM exit (processing block 308). Otherwise, processing logic returns to processing block 302. Depending on the nature of the non-VMM timer event (e.g., whether the non-VMM timer event is an external interrupt or an internal event), exiting the VM may or may not be followed by the event handling procedure.

In one embodiment, the comparison between the current time and the VMM timer value (illustrated in processing box 302) is performed after each cycle executed by the VM, until the current time meets or exceeds the VMM timer value.

In an embodiment, the comparison is performed in a hardware component, which is configured to generate a signal if the current time matches the VMM timer value. The signal indicates that a VM exit should be generated due to the VMM timer. In one embodiment, the signal is recognized (e.g., by microcode or another hardware component) at the end of the currently executing instruction. The recognized signal indicates that a VM exit due to the VMM timer may be required. This requirement is then prioritized (e.g., by microcode or another hardware component) with other VM exit sources, and the appropriate VM exit to the VMM is generated. That is, if the VMM timer source is of higher priority than other VM exit sources, a VM exit due to the VMM timer is generated. If a VM exit source other than the VMM timer is of higher priority than the VMM timer, a VM exit due to this other source is generated.

Referring to FIG. 4, process 400 uses a VMM timer value that specifies an offset value indicating how long the VM is allowed to execute. Process 400 begins subsequent to determining that the VMM timer is enabled and identifying a VMM timer value configured by the VMM, as illustrated in FIG. 2.

Initially, processing logic stores the offset value configured by the VMM (e.g., as stored in a preemption timer field in the VMCS) as a countdown value in a register (processing block 402). Next, processing logic transitions control to the VM (processing block 403). After transitioning control to the VM, processing logic begins decrementing the countdown value at the rate proportional to the increments of the clock (e.g., every N ticks of the clock) (processing block 404). After each decrement, processing logic checks whether the countdown value has reached 0 (processing box 406). Note that the decrementing of the countdown value may result in the value becoming negative. In this case, in an embodiment, the value is not allowed to be made lower than 0 (i.e., the decrementing stops at 0). Alternatively, the value may be allowed to be made lower than 0, in which case the determination at processing block 406 would be made determined by the value reaching or crossing 0. If the countdown value has reached (has matched or crossed) 0, processing logic issues an internal event and generates a VM exit, indicating that the source of the VM exit is the VMM timer (processing block 412). In one embodiment, once the determination in processing block 406 is positive, a signal is generated that is recognized (e.g., by microcode or a hardware component) at the end of the currently executing instruction. The recognition of this signal indicates that a VM exit due to the VMM timer may be required. This requirement is then prioritized (e.g., by microcode) with other VM exit sources, and the appropriate VM exit to the VMM is generated as discussed above.

If the countdown value has not yet reached 0, processing logic checks for a non-VMM timer event associated with a VM exit (processing box 408). If such event occurs, processing logic stores the current countdown value to the VMCS (processing block 410) and generates a VM exit, indicating the source of this VM exit (processing block 414). Otherwise, processing logic returns to processing block 404.

In an embodiment, the storing of the countdown timer value in processing block 410 may be controlled by a store VMM timer control value stored in the VMCS. If the store VMM timer control is set to an enabled value, then the value of the countdown timer is stored (e.g., to the VMCS) as part of VM exit processing. In an embodiment, if the store VMM timer control is not set to an enabled value, a value of 0 is stored to the offset value configured by the VMM (e.g., to a field in the VMCS). In another embodiment, if the store VMM timer control is not set to an enabled value the offset value configured by the VMM is not modified.

FIG. 5 is a flow diagram of one embodiment of a process 500 for configuring a timer associated with a VMM. The process may be performed by processing logic that may comprise hardware (e.g., circuitry, dedicated logic, programmable logic, microcode, etc.), software (such as that run on a general purpose computer system or a dedicated machine), or a combination of both. In one embodiment, process 500 is performed by a timer configuration module 126 of FIG. 1.

Referring to FIG. 5, process 500 begins with processing logic determining a VMM timer value (processing block 502) and storing it in the VMCS (processing block 504). In one embodiment, the VMM timer value specifies the time at which control should be returned to the VMM. Examples of calculating the VMM timer value are provided below.

Next, processing logic sets a VMM timer indicator to an enabling value (processing block 506) and issues a request to transition control to the VM (a VM entry request) (processing logic 508).

Subsequently, when a VM exit from the VM is generated, processing logic receives control back (processing block 510) and determines whether control was returned due to the VMM timer (processing block 512). If so, processing logic may perform a desired operation and then generate a VM entry to the same VM or a different VM.

Prior to generating the VM entry, processing logic may need to update the VM timer indicator and/or the VMM timer value (processing block 514). In one embodiment, the remaining time was saved to the VMCS prior to the VM exit (as discussed above with respect to FIG. 4). In another embodiment, the remaining time is calculated by processing logic upon receiving control from the VM.

In an embodiment, the VMM timer is used to determine a scheduling quantum for a VM. When a VM is scheduled to execute, it is assigned a quantum value by the VMM. This value is initially used for the VMM timer value. Upon transition to the VM, processing logic will utilize the countdown VMM timer value as described with respect to FIG. 4. Before control is transitioned to the VMM, processing logic determines how much time was left in the time quantum allocated to the VM. In one embodiment, processing logic calculates the remaining time by reading the time value of the timing source prior to transitioning control to the VM and when receiving control from the VM. The difference of these two values indicates how long the VM was executing. This value is then subtracted from the time allocated to the VM. When the remaining time value reaches 0, the VMs scheduling quantum is consumed, and the VMM may then schedule a different VM to execute.

In one embodiment, the VMM timer value is used to limit the maximum time that may be spent in the VM. An offset value (i.e., a time interval specifying how long the VM is allowed to execute) is added to the value of the timing source read by the VMM at the time of calculation. This value is used as the VMM timer value. Upon transition to the VM, processing logic will utilize this value as described with respect to FIG. 3. This same value is used each time control is transitioned to the VM. In this embodiment, the VMM timer acts as a watchdog timer, limiting the longest execution time in the VM, in the absence of other VM exit sources. Note that in an embodiment, a countdown timer (as described with respect to FIG. 4) may also be utilized to realize a watchdog timer mechanism.

Thus, a method and apparatus for providing support for a timer associated with a VMM have been described. It is to be understood that the above description is intended to be illustrative, and not restrictive. Many other embodiments will be apparent to those of skill in the art upon reading and understanding the above description. The scope of the invention should, therefore, be determined with reference to the appended claims, along with the full scope of equivalents to which such claims are entitled.