__str__,__repr__

- __str__定义在类内部,必须返回一个字符串类型

- __repr__定义在类内部,必须返回一个字符串类型

- 打印由这个类产生的对象时,会触发执行__str__,如果没有__str__会触发__repr__

class Bar: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age # def __str__(self): # print("this str") # return "名字是%s age%s" % (self.name, self.age) def __repr__(self): # 转换字符串,在解释器中执行 print("thsi repr") return "%s" % self.name test = Bar("alex", 18) print(test) #__str__定义在类内部,必须返回一个字符串类型, #__repr__定义在类内部,必须返回一个字符串类型, #打印由这个类产生的对象时,会触发执行__str__,如果没有__str__会触发__repr__ class B: def __str__(self): return 'str : class B' def __repr__(self): return 'repr : class B' b = B() print(b) #str : class B print('%s' % b) #str : class B print('%r' % b) #repr : class B

反射

- 通过字符串的形式操作对象相关的属性。python中的一切事物都是对象(都可以使用反射)

class Foo: f = '类的静态变量' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say_hi(self): print('hi,%s'%self.name) obj=Foo('egon',73) #检测是否含有某属性 print(hasattr(obj,'name')) print(hasattr(obj,'say_hi')) #获取属性 n=getattr(obj,'name') print(n) func=getattr(obj,'say_hi') func() print(getattr(obj,'aaaaaaaa','不存在啊')) #报错 #设置属性 setattr(obj,'sb',True) setattr(obj,'show_name',lambda self:self.name+'sb') print(obj.__dict__) print(obj.show_name(obj)) #删除属性 delattr(obj,'age') delattr(obj,'show_name') delattr(obj,'show_name111')#不存在,则报错 print(obj.__dict__)

class Foo(object): staticField = "old boy" def __init__(self): self.name = 'wupeiqi' def func(self): return 'func' @staticmethod def bar(): return 'bar' print getattr(Foo, 'staticField') print getattr(Foo, 'func') print getattr(Foo, 'bar')

import sys def s1(): print 's1' def s2(): print 's2' this_module = sys.modules[__name__] hasattr(this_module, 's1') getattr(this_module, 's2')

#module_test.py中 def test(): print('from the test') """ 程序目录: module_test.py index.py 当前文件: index.py """ import module_test as obj # obj.test() print(hasattr(obj, 'test')) getattr(obj, 'test')()

isinstance(obj,cls)和issubclass(sub,super)

- isinstance(obj,cls)检查对象(obj)是否是类(类的对象)

- issubclass(sub, super)检查字(sub)类是否是父( super) 类的派生类

class Bar: pass class Foo(Bar): pass obj=Foo() print(isinstance(obj,Foo)) print(Foo.__bases__) print(issubclass(Foo,Bar)) """ True (<class '__main__.Bar'>,) True """

type

- type(obj) 表示查看obj是由哪个类创建的。

class Foo: pass obj = Foo() # 查看obj的类 print(obj, type(obj)) #<__main__.Foo object at 0x0000000000B1B7B8> <class '__main__.Foo'>

attr系列

- __getattr__只有在使用点调用属性且属性不存在的时候才会触发

- __setattr__添加/修改属性会触发它的执行

- __delattr__删除属性的时候会触发

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.name=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('----> from getattr:你找的属性不存在') def __setattr__(self, key, value): #这的key类型是str print('----> from setattr') # if not isinstance(value,str): # raise TypeError('must be str') #setattr(self,key,value)和 self.key=value #这就无限递归了,你好好想想 self.__dict__[key]=value def __delattr__(self, item): #这的item类型是str print('----> from delattr') # delattr(self,item)和 del self.item #这就无限递归了 self.__dict__.pop(item) # __setattr__添加/修改属性会触发它的执行 f1 = Foo('alex') #设置属性 触发__setattr__ print(f1.__dict__) # 因为你重写了__setattr__,凡是赋值操作都会触发它的运行,你啥都没写,就是根本没赋值,除非你直接操作属性字典,否则永远无法赋值 f1.z = 3 # 添加属性 触发__setattr__ print(f1.__dict__) setattr(f1,'nn',55) #添加属性 触发__setattr__ print(f1.__dict__) f1.__dict__['a'] = 3 # 可以直接修改属性字典,来完成添加/修改属性的操作,这样的操作不触发__setattr__ print(f1.__dict__) # __delattr__删除属性的时候会触发 del f1.a #触发__delattr__ print(f1.__dict__) delattr(f1,'nn') #触发__delattr__ print(f1.__dict__) f1.__dict__.pop('z') #不触发__delattr__ print(f1.__dict__) # __getattr__只有在使用点调用属性且属性不存在的时候才会触发 f1.xxxxxx

__getattr__和__getattribute__

- 当__getattribute__与__getattr__同时存在,只会执行__getattrbute__,除非__getattribute__在执行过程中抛出异常AttributeError

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('执行的是我') # return self.__dict__[item] f1=Foo(10) print(f1.x) f1.xxxxxx #不存在的属性访问,触发__getattr__ """ 10 执行的是我 """ class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattribute__(self, item): print('不管是否存在,我都会执行') f1=Foo(10) f1.x f1.xxxxxx """ 不管是否存在,我都会执行 不管是否存在,我都会执行 """ class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('执行的是我') # return self.__dict__[item] def __getattribute__(self, item): print('不管是否存在,我都会执行') raise AttributeError('哈哈') f1=Foo(10) f1.x f1.xxxxxx """ 不管是否存在,我都会执行 执行的是我 不管是否存在,我都会执行 执行的是我 """

二次加工标准类型(包装)

1、基于继承的原理定制自己的数据类型

包装:python为大家提供了标准数据类型,以及丰富的内置方法,其实在很多场景下我们都需要基于标准数据类型来定制我们自己的数据类型,新增/改写方法,这就用到了我们刚学的继承/派生知识(其他的标准类型均可以通过下面的方式进行二次加工)

class List(list): #继承list所有的属性,也可以派生出自己新的,比如append和mid def append(self, p_object): ' 派生自己的append:加上类型检查' if not isinstance(p_object,int): raise TypeError('must be int') super().append(p_object) @property def mid(self): '新增自己的属性' index=len(self)//2 return self[index] l=List([1,2,3,4]) print(l) l.append(5) print(l) # l.append('1111111') #报错,必须为int类型 print(l.mid) #其余的方法都继承list的 l.insert(0,-123) print(l) l.clear() print(l)

2、授权的方式实现定制自己的数据类型

授权:授权是包装的一个特性, 包装一个类型通常是对已存在的类型的一些定制,这种做法可以新建,修改或删除原有产品的功能。其它的则保持原样。授权的过程,即是所有更新的功能都是由新类的某部分来处理,但已存在的功能就授权给对象的默认属性。 实现授权的关键点就是覆盖__getattr__方法

import time class FileHandle: def __init__(self,filename,mode='r',encoding='utf-8'): self.file=open(filename,mode,encoding=encoding) def write(self,line): t=time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %T') self.file.write('%s %s' %(t,line)) def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.file,item) f1=FileHandle('b.txt','w+') f1.write('你好啊') f1.seek(0) print(f1.read()) f1.close()

class List: def __init__(self,x): self.seq=list(x) def append(self,value): if not isinstance(value,str): raise TypeError('must be str') self.seq.append(value) @property def mid(self): index=len(self.seq)//2 return self.seq[index] def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.seq,item) def __str__(self): return str(self.seq) l=List([1,2,3]) l.append('1') print(l.mid) l.insert(0,123123123123123123123123123) # print(l.seq) print(l)

item系列

- 通过字典方式,查看修改,类或者对象的属性

- __setitem__,__getitem,__delitem__

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name # 参数类型是字符串 def __getitem__(self, item): print('getitem',type(item)) print(self.__dict__[item]) def __getattr__(self, item): print('----> from getattr:你找的属性不存在') def __setitem__(self, key, value): print('setitem',type(key)) self.__dict__[key]=value def __setattr__(self, key, value): print('----> from setattr',type(key)) self.__dict__[key] = value def __delitem__(self, key): print('del obj[key]时,我执行',type(key)) self.__dict__.pop(key) def __delattr__(self, item): print('----> from delattr del obj.key时,我执行',type(item)) self.__dict__.pop(item) #触发__setattr__ f1=Foo('sb') f1.gender='male' setattr(f1,'level','high') #触发__setitem__ f1['age']=18 f1['age1']=19 #触发__delattr__ del f1.age1 delattr(f1,'level') #触发__delitem__ del f1['age'] #触发__getattr__ f1.xxxxxx #触发__getitem__ f1['name'] #什么都不触发 f1.__dict__['test']='aa' f1.__dict__['test'] f1.__dict__.pop('test') print(f1.__dict__)

__format__

- 自定制格式化字符串__format__

#!/usr/bin/env python # -*- coding: utf-8 -*- format_dict={ 'nat':'{obj.name}-{obj.addr}-{obj.type}',#学校名-学校地址-学校类型 'tna':'{obj.type}:{obj.name}:{obj.addr}',#学校类型:学校名:学校地址 'tan':'{obj.type}/{obj.addr}/{obj.name}',#学校类型/学校地址/学校名 } class School: def __init__(self,name,addr,type): self.name=name self.addr=addr self.type=type def __repr__(self): return 'School(%s,%s)' %(self.name,self.addr) def __str__(self): return '(%s,%s)' %(self.name,self.addr) def __format__(self, format_spec): # if format_spec if not format_spec or format_spec not in format_dict: format_spec='nat' fmt=format_dict[format_spec] return fmt.format(obj=self) s1=School('oldboy1','北京','私立') print('from repr: ',repr(s1)) #from repr: School(oldboy1,北京) print('from str: ',str(s1)) #from str: (oldboy1,北京) print(s1) #(oldboy1,北京) ''' str函数或者print函数--->obj.__str__() repr或者交互式解释器--->obj.__repr__() 如果__str__没有被定义,那么就会使用__repr__来代替输出 注意:这俩方法的返回值必须是字符串,否则抛出异常 ''' print(format(s1,'nat')) #oldboy1-北京-私立 print(format(s1,'tna')) #私立:oldboy1:北京 print(format(s1,'tan')) #私立/北京/oldboy1 print(format(s1,'asfdasdffd')) #oldboy1-北京-私立

# 和生成实例化对象的内容相对应 date_dic={ 'ymd':'{0.year}:{0.month}:{0.day}', 'dmy':'{0.day}/{0.month}/{0.year}', 'mdy':'{0.month}-{0.day}-{0.year}', } class Date: def __init__(self,year,month,day): self.year=year self.month=month self.day=day def __format__(self, format_spec): # format_spec指定格式化的类型 if not format_spec or format_spec not in date_dic: format_spec='ymd' fmt=date_dic[format_spec] # 通过date_dic字典格式化成相应格式的类型 return fmt.format(self) #把对象传入,格式化的内容 d1=Date(2016,12,29) print(format(d1)) print('{:mdy}'.format(d1)) """ 2016-12-26 20161226 """

class Student: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age # 定义对象的字符串表示 def __str__(self): return self.name def __repr__(self): return self.name __format_dict = { 'n-a': '{obj.name}-{obj.age}', # 姓名-年龄 'n:a': '{obj.name}:{obj.age}', # 姓名:年龄 'n/a': '{obj.name}/{obj.age}', # 姓名/年龄 } def __format__(self, format_spec): """ :param format_spec: n-a,n:a,n/a :return: """ if not format_spec or format_spec not in self.__format_dict: format_spec = 'n-a' fmt = self.__format_dict[format_spec] return fmt.format(obj=self) s1 = Student('张三', 24) ret = format(s1, 'n/a') print(ret) # 张三/24

__dict__和__slots__

- Python中的类,都会从object里继承一个__dict__属性,这个属性中存放着类的属性和方法对应的键值对。一个类实例化之后,这个类的实例也具有这么一个__dict__属性。但是二者并不相同。

- __slots__是什么:是一个类变量,变量值可以是列表,元祖,或者可迭代对象,也可以是一个字符串(意味着所有实例只有一个数据属性)

- 引子:使用点来访问属性本质就是在访问类或者对象的__dict__属性字典(类的字典是共享的,而每个实例的是独立的)

- 为何使用__slots__:字典会占用大量内存,如果你有一个属性很少的类,但是有很多实例,为了节省内存可以使用__slots__取代实例的__dict__ 当你定义__slots__后,__slots__就会为实例使用一种更加紧凑的内部表示。实例通过一个很小的固定大小的数组来构建,而不是为每个实例定义一个 字典,这跟元组或列表很类似。在__slots__中列出的属性名在内部被映射到这个数组的指定小标上。使用__slots__一个不好的地方就是我们不能再给 实例添加新的属性了,只能使用在__slots__中定义的那些属性名。

- 注意事项:__slots__的很多特性都依赖于普通的基于字典的实现。另外,定义了__slots__后的类不再 支持一些普通类特性了,比如多继承。大多数情况下,你应该 只在那些经常被使用到 的用作数据结构的类上定义__slots__比如在程序中需要创建某个类的几百万个实例对象 。 关于__slots__的一个常见误区是它可以作为一个封装工具来防止用户给实例增加新的属性。尽管使用__slots__可以达到这样的目的,但是这个并不是它的初衷。

class A: some = 1 def __init__(self, num): self.num = num def eat(self): print('eat') a = A(10) print(a.__dict__) # {'num': 10} a.age = 10 print(a.__dict__) # {'num': 10, 'age': 10} print(A.__dict__) """ { '__module__': '__main__', 'some': 1, 'eat': <function A.eat at 0x00000000043ED950>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'A' objects>, '__doc__': None, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'A' objects>, '__init__': <function A.__init__ at 0x0000000000C079D8> } """ """ 从上面的例子可以看出来,实例只保存实例的属性,类的属性和方法它是不保存的。正是由于类和实例有__dict__属性,所以类和实例可以在运行过程动态添加属性和方法。 但是由于每实例化一个类都要分配一个__dict__变量,容易浪费内存。因此在Python中有一个内置的__slots__属性。当一个类设置了__slots__属性后,这个类的__dict__属性就不存在了(同理,该类的实例也不存在__dict__属性),如此一来,设置了__slots__属性的类的属性,只能是预先设定好的。 当你定义__slots__后,__slots__就会为实例使用一种更加紧凑的内部表示。实例通过一个很小的固定大小的小型数组来构建的,而不是为每个实例都定义一个__dict__字典,在__slots__中列出的属性名在内部被映射到这个数组的特定索引上。使用__slots__带来的副作用是我们没有办法给实例添加任何新的属性了。 注意:尽管__slots__看起来是个非常有用的特性,但是除非你十分确切的知道要使用它,否则尽量不要使用它。比如定义了__slots__属性的类就不支持多继承。__slots__通常都是作为一种优化工具来使用。--摘自《Python Cookbook》8.4 """ class A: __slots__ = ['name', 'age'] a1 = A() # print(a1.__dict__) # AttributeError: 'A' object has no attribute '__dict__' a1.name = '张三' a1.age = 24 # a1.hobby = '吹牛逼' # AttributeError: 'A' object has no attribute 'hobby' print(a1.__slots__) #['name', 'age'] """ 注意事项: __slots__的很多特性都依赖于普通的基于字典的实现。 另外,定义了__slots__后的类不再 支持一些普通类特性了,比如多继承。大多数情况下,你应该只在那些经常被使用到的用作数据结构的类上定义__slots__,比如在程序中需要创建某个类的几百万个实例对象 。 关于__slots__的一个常见误区是它可以作为一个封装工具来防止用户给实例增加新的属性。尽管使用__slots__可以达到这样的目的,但是这个并不是它的初衷。它更多的是用来作为一个内存优化工具。 """

class Poo: __slots__ = 'x' p1 = Poo() p1.x = 1 # p1.y = 2 # 报错 print(p1.__slots__) #打印x p1不再有__dict__ class Bar: __slots__ = ['x', 'y'] n = Bar() n.x, n.y = 1, 2 # n.z = 3 # 报错 print(n.__slots__) #打印['x', 'y'] class Foo: __slots__=['name','age'] f1=Foo() f1.name='alex' f1.age=18 print(f1.__slots__) #['name', 'age'] f2=Foo() f2.name='egon' f2.age=19 print(f2.__slots__) #['name', 'age'] print(Foo.__dict__)#f1与f2都没有属性字典__dict__了,统一归__slots__管,节省内存 """ { 'age': <member 'age' of 'Foo' objects>, 'name': <member 'name' of 'Foo' objects>, '__module__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__slots__': ['name', 'age']}ame', 'age'] } """

__next__和__iter__实现迭代器协议

- 如果一个对象拥有了__iter__和__next__方法,那这个对象就是可迭代对象。

class A: def __init__(self, start, stop=None): if not stop: start, stop = 0, start self.start = start self.stop = stop def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): if self.start >= self.stop: raise StopIteration n = self.start self.start += 1 return n a = A(1, 5) from collections import Iterator print(isinstance(a, Iterator)) for i in A(1, 5): print(i) for i in A(5): print(i) """ True 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 3 4 """

class Foo: def __init__(self,start,stop): self.num=start self.stop=stop def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): if self.num >= self.stop: raise StopIteration n=self.num self.num+=1 return n f=Foo(1,5) from collections import Iterable,Iterator print(isinstance(f,Iterator)) for i in Foo(1,5): print(i) """ True 1 2 3 4 """

class Range: def __init__(self,start,end,step): self.start=start self.end=end self.step=step def __next__(self): if self.start >= self.end: raise StopIteration x=self.start self.start+=self.step return x def __iter__(self): return self for i in Range(1,7,2): print(i) #1 3 5

class Fib: def __init__(self): self._a=0 self._b=1 def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): self._a,self._b=self._b,self._a + self._b return self._a f1=Fib() print(f1.__next__()) print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) for i in f1: if i > 100: break print('%s ' %i,end='') ''' 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 '''

__module__和__class__

- __module__ 表示当前操作的对象在那个模块

- __class__ 表示当前操作的对象的类是什么

#test.py class C: def __init__(self): self.name = '测试' #aa.py from test import C class Foo: pass f1 = Foo() print(f1.__module__) #__main__ print(f1.__class__) #<class '__main__.Foo'> c1 = C() print(c1.__module__) #test 即:输出模块 print(c1.__class__) #<class 'test.C'> 即:输出类

__del__析构方法

- 情况1:当对象在内存中被释放时,自动触发执行。

- 情况2:人为主动del f对象时(如果引用计数为零时),自动触发执行。

- 注:此方法一般无须定义,因为Python是一门高级语言,程序员在使用时无需关心内存的分配和释放,因为此工作都是交给Python解释器来执行,所以析构函数的调用是由解释器在进行垃圾回收时自动触发执行的。

- 注:如果产生的对象仅仅只是python程序级别的(用户级),那么无需定义__del__,如果产生的对象的同时还会向操作系统发起系统调用,即一个对象有用户级与内核级两种资源,比如(打开一个文件,创建一个数据库链接),则必须在清除对象的同时回收系统资源,这就用到了__del__

- 典型的应用场景:

- 数据库链接对象被删除前向操作系统发起关闭数据库链接的系统调用,回收资源

- 在del f之前保证f.close()执行

class Foo: def __del__(self): print('执行我啦') f1=Foo() del f1 print('------->') """ 执行我啦 -------> """ class Foo: def __del__(self): print('执行我啦') f1=Foo() # del f1 print('------->') """ -------> 执行我啦 """

""" 典型的应用场景: 创建数据库类,用该类实例化出数据库链接对象,对象本身是存放于用户空间内存中,而链接则是由操作系统管理的,存放于内核空间内存中 当程序结束时,python只会回收自己的内存空间,即用户态内存,而操作系统的资源则没有被回收,这就需要我们定制__del__, 在对象被删除前向操作系统发起关闭数据库链接的系统调用,回收资源 这与文件处理是一个道理: f=open('a.txt') #做了两件事,在用户空间拿到一个f变量,在操作系统内核空间打开一个文件 del f #只回收用户空间的f,操作系统的文件还处于打开状态 #所以我们应该在del f之前保证f.close()执行,即便是没有del,程序执行完毕也会自动del清理资源,于是文件操作的正确用法应该是 f=open('a.txt') #读写... f.close() #很多情况下大家都容易忽略f.close,这就用到了with上下文管理 """ import time class Open: def __init__(self,filepath,mode='r',encode='utf-8'): self.f=open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encode) def write(self): pass def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.f,item) def __del__(self): print('----->del') self.f.close() ## f=Open('a.txt','w') f1=f del f #f1=f 引用计数不为零 print('=========>') """ =========> ----->del """

__len__

- 拥有__len__方法的对象支持len(obj)操作。

class A: def __init__(self): self.x = 1 self.y = 2 def __len__(self): return len(self.__dict__) a = A() print(len(a)) #2

__hash__

- 拥有__hash__方法的对象支持hash(obj)操作。

class A: def __init__(self): self.x = 1 self.x = 2 def __hash__(self): return hash(str(self.x) + str(self.x)) a = A() print(hash(a)) #148652591932004211

__mro__

- 对于我们定义的每一个类,Python会计算出一个方法解析顺序(Method Resolution Order, MRO)列表,它代表了类继承的顺序。

- super()函数所做的事情就是在MRO列表中找到当前类的下一个类。

class A: def __init__(self): print('进入A类') print('离开A类') class B(A): def __init__(self): print('进入B类') super().__init__() print('离开B类') class C(A): def __init__(self): print('进入C类') super().__init__() print('离开C类') class D(B, C): def __init__(self): print('进入D类') super().__init__() print('离开D类') class E(D): def __init__(self): print('进入E类') super().__init__() print('离开E类') print(E.__mro__) #(<class '__main__.E'>, <class '__main__.D'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <class '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class 'object'>) """ 那这个 MRO 列表的顺序是怎么定的呢,它是通过一个 C3 线性化算法来实现的, 简单来说,一个类的 MRO 列表就是合并所有父类的 MRO 列表,并遵循以下三条原则: 1.子类永远在父类前面 2.如果有多个父类,会根据它们在列表中的顺序被检查 3.如果对下一个类存在两个合法的选择,选择第一个父类 super()函数所做的事情就是在MRO列表中找到当前类的下一个类。 """

super()

class A: def func(self): print('OldBoy') class B(A): def func(self): super().func() print('LuffyCity') A().func() B().func() """ A实例化的对象调用了func方法,打印输出了 Oldboy; B实例化的对象调用了自己的func方法,先调用了父类的方法打印输出了 OldBoy ,再打印输出 LuffyCity 输出的结果为: OldBoy OldBoy LuffyCity 如果不使用super的话,想得到相同的输出截个,还可以这样写B的类: class B(A): def func(self): A.func(self) print('LuffyCity') 这样能实现相同的效果,只不过传了一个self参数。那为什么还要使用super()呢? """ class Base: def __init__(self): print('Base.__init__') class A(Base): def __init__(self): Base.__init__(self) print('A.__init__') class B(Base): def __init__(self): Base.__init__(self) print('B.__init__') class C(A, B): def __init__(self): A.__init__(self) B.__init__(self) print('C.__init__') C() """ Base / \ / \ A B \ / \ / C 输出的结果是: Base.__init__ A.__init__ Base.__init__ B.__init__ C.__init__ Base类的__init__方法被调用了两次,这是多余的操作,也是不合理的。 改写成使用super()的写法: """ class Base: def __init__(self): print('Base.__init__') class A(Base): def __init__(self): super().__init__() print('A.__init__') class B(Base): def __init__(self): super().__init__() print('B.__init__') class C(A, B): def __init__(self): super().__init__() print('C.__init__') C() """ 输出的结果是: Base.__init__ B.__init__ A.__init__ C.__init__ print(C.mro()) # [<class '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <class '__main__.Base'>, <class 'object'>] """ print(super(C)) #<super: <class 'C'>, NULL> # print(super()) #报错 RuntimeError: super(): no arguments #用法1: #在定义类当中可以不写参数,Python会自动根据情况将两个参数传递给super,所以我们在类中使用super的时候参数是可以省略的。 class C(A, B): def __init__(self): print(super()) #<super: <class 'C'>, <C object>> super().__init__() print('C.__init__') C() #用法2: #super(type, obj) 传递一个类和对象,得到的是一个绑定的super对象。这还需要obj是type的实例,可以不是直接的实例,是子类的实例也行。 a = A() print(super(A, a)) #<super: <class 'A'>, <A object>> print(super(Base, a)) #<super: <class 'Base'>, <A object>> class C(A, B): def __init__(self): super(C, self).__init__() # 与 super().__init__() 效果一样 print('C.__init__') C() """ 输出结果: Base.__init__ B.__init__ A.__init__ C.__init__ """ class C(A, B): def __init__(self): super(A, self).__init__() print('C.__init__') C() """ 输出结果: Base.__init__ B.__init__ C.__init__ 那A.__init__怎么跑丢了呢? 这是应为Python是按照第二个参数来计算MRO,这次的参数是self,也就是C的MRO。在这个顺序中跳过一个参数(A)找后面一个类(B),执行他的方法。 """ #用法3: #super(type, type2)传递两个类,得到的也是一个绑定的super对象。这需要type2是type的子类。 print(super(Base, A)) #<super: <class 'Base'>, <A object>> print(super(Base, B)) #<super: <class 'Base'>, <B object>> print(super(Base, C)) #<super: <class 'Base'>, <C object>> #说说 super(type, obj) 和 super(type, type2)的区别 class Base: def func(self): return 'from Base' class A(Base): def func(self): return 'from A' class B(Base): def func(self): return 'from B' class C(A, B): def func(self): return 'from C' c_obj = C() print(super(C, C)) #<super: <class 'C'>, <C object>> print(super(C, c_obj)) #<super: <class 'C'>, <C object>> print(super(C, C).func is super(C, c_obj).func) #False print(super(C, C).func == super(C, c_obj).func) #False c1 = super(C, C) c2 = super(C, C) print(c1 is c2) #False print(c1 == c2) #False print(c1.func is c2.func) #True print(c1.func == c2.func) #True c1 = super(C, C) c2 = super(C, c_obj) print(c1 is c2) #False print(c1 == c2) #False print(c1.func is c2.func) #False print(c1.func == c2.func) #False print(super(C, C).func) #<function A.func at 0x0000000012E08268> print(super(C, c_obj).func) #<bound method A.func of <__main__.C object at 0x0000000012DE8D68>> print(super(C, C).func(c_obj)) #from A print(super(C, c_obj).func()) #from A """ super的第二个参数传递的是类,得到的是函数。 super的第二个参数传递的是对象,得到的是绑定方法。 --super--可以访问MRO列表中的下一个类中的内容,找父类。 不管super()写在那,在那执行,一定先找到MRO列表,根据MRO列表的顺序往下找,否则一切都是错的。 super()使用的时候需要传递两个参数,在类中可以省略不写,我们使用super()来找父类或者兄弟类的方法; super()是根据第二个参数来计算MRO,根据顺序查找第一个参数类后的方法。 super()第二个参数是类,得到的方法是函数,使用时要传self参数。第二个参数是对象,得到的是绑定方法,不需要再传self参数。 给使用super()的一些建议: super()调用的方法要存在; 传递参数的时候,尽量使用*args 与**kwargs; 父类中的一些特性,比如【】、重写了__getattr__,super对象是不能使用的。 super()第二个参数传的是类的时候,建议调用父类的类方法和静态方法。 """

__eq__

- 拥有__eq__方法的对象支持相等的比较操作。

class Person: def __init__(self,name,age,sex): self.name = name self.age = age self.sex = sex def __hash__(self): return hash(self.name+self.sex) def __eq__(self, other): if self.name == other.name and self.sex == other.sex:return True p_lst = [] for i in range(84): p_lst.append(Person('egon',i,'male')) print(p_lst) print(set(p_lst))

class A: def __init__(self): self.x = 1 self.y = 2 def __eq__(self,obj): if self.x == obj.x and self.y == obj.y: return True a = A() b = A() print(a == b) #True

__enter__和__exit__实现上下文管理协议

- 一个对象如果实现了__enter__和___exit__方法,那么这个对象就支持上下文管理协议,即with语句。

- 上下文管理协议适用于那些进入和退出之后自动执行一些代码的场景,比如文件、网络连接、数据库连接或使用锁的编码场景等。

- with语句(也叫上下文管理协议),为了让一个对象兼容with语句,必须在这个对象的类中声明__enter__和__exit__方法

- __exit__()中的三个参数分别代表异常类型(exc_type),异常值(exc_val)和追溯信息(exc_tb),即with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行

- 如果__exit()返回值为True,那么异常会被清空,就好像啥都没发生一样,with后的语句正常执行

- 用途或者说好处:

- 使用with语句的目的就是把代码块放入with中执行,with结束后,自动完成清理工作,无须手动干预

- 在需要管理一些资源比如文件,网络连接和锁的编程环境中,可以在__exit__中定制自动释放资源的机制

class A: def __enter__(self): print('进入with语句块时执行此方法,此方法如果有返回值会赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): """ :param exc_type: 异常类型 :param exc_val: 异常值 :param exc_tb: 追溯信息 :return: """ print('退出with代码块时执行此方法') print('1', exc_type) print('2', exc_val) print('3', exc_tb) with A() as f: print('进入with语句块') # with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行。 # raise AttributeError('sb') print('嘿嘿嘿') """ 进入with语句块时执行此方法,此方法如果有返回值会赋值给as声明的变量 进入with语句块 退出with代码块时执行此方法 1 None 2 None 3 None 嘿嘿嘿 """

""" with open('a.txt') as f: '代码块' 上述叫做上下文管理协议,即with语句,为了让一个对象兼容with语句,必须在这个对象的类中声明__enter__和__exit__方法 __exit__的运行完毕就代表了整个with语句的执行完毕 """ class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') # print(f,f.name) #__enter__方法的返回值赋值给as声明的变量 """ 出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量 =====>执行代码块 with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊 """ #__exit__()中的三个参数分别代表异常类型,异常值和追溯信息,with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行 class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') #遇到raise,with里代码就结束,with代码块里raise后面的代码就不会执行,with代码结束就会执行__exit__方法 print('11111111') ####永远不会打印 print('0'*100) #------------------------------->不会执行 #如果__exit()返回值为True,那么异常会被清空,就好像啥都没发生一样,with后的语句正常执行 class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) return True #有返回值 with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') print('11111111') ####永远不会打印 print('0'*100) #------------------------------->会执行 #__exit__方法返回布尔值为true的值时,with代码块后面的代码会执行

class Open: def __init__(self,filepath,mode,encode='utf-8'): self.f=open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encode) self.filepath=filepath self.mode=mode self.encoding=encode def write(self,line): print('write') self.f.write(line) def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.f,item) def __enter__(self): return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() return True with Open('a.txt','w') as f: #f=Open('a.txt','w') f.write('11\n') f.write('22\n') print(sssssssssssssss) #抛出异常,交给__exit__处理 f.write('33\n') # 这不执行 print('aaaaa')#执行

class A: def __enter__(self): print('before') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('after') with A() as a: print('123') """ before 123 after """

class A: def __init__(self): print('init') def __enter__(self): print('before') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('after') with A() as a: print('123') """ init before 123 after """

class Myfile: def __init__(self,path,mode='r',encoding = 'utf-8'): self.path = path self.mode = mode self.encoding = encoding def __enter__(self): self.f = open(self.path, mode=self.mode, encoding=self.encoding) return self.f def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() with Myfile('file',mode='w') as f: f.write('wahaha')

import pickle class MyPickledump: def __init__(self,path): self.path = path def __enter__(self): self.f = open(self.path, mode='ab') return self def dump(self,content): pickle.dump(content,self.f) def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() class Mypickleload: def __init__(self,path): self.path = path def __enter__(self): self.f = open(self.path, mode='rb') return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() def load(self): return pickle.load(self.f) def loaditer(self): while True: try: yield self.load() except EOFError: break # with MyPickledump('file') as f: # f.dump({1,2,3,4}) with Mypickleload('file') as f: for item in f.loaditer(): print(item)

import pickle class MyPickledump: def __init__(self,path): self.path = path def __enter__(self): self.f = open(self.path, mode='ab') return self def dump(self,content): pickle.dump(content,self.f) def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() class Mypickleload: def __init__(self,path): self.path = path def __enter__(self): self.f = open(self.path, mode='rb') return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): self.f.close() def __iter__(self): while True: try: yield pickle.load(self.f) except EOFError: break # with MyPickledump('file') as f: # f.dump({1,2,3,4}) with Mypickleload('file') as f: for item in f: print(item)

property

- 一个静态属性property本质就是实现了get,set,delete三种方法

#被property装饰的属性会优先于对象的属性被使用,只有在属性sex定义property后才能定义sex.setter,sex.deleter class People: def __init__(self,name,SEX): self.name=name # self.__sex=SEX #这不调用@sex.setter def sex(self,value):方法 因为设置的是__sex 不是 sex,或者说__sex没有被@property装饰 self.sex=SEX #①因为sex被@property装饰,所以self.sex=SEX是去找@sex.setter def sex(self,value): 方法,而不是给对象赋值 @property def sex(self): return self.__sex #p1.__sex @sex.setter def sex(self,value): print('...') if not isinstance(value,str): raise TypeError('性别必须是字符串类型') self.__sex=value #② male给了value , self.__sex='male' @sex.deleter #del p1.sex的时候调用 def sex(self): del self.__sex #del p1.__sex p1=People('alex','male') #会调用 @sex.setter def sex(self,value): 方法是因为__init__中 self.sex=SEX 是给sex设置值了 p1.sex='female' #会调用@sex.setter def sex(self,value): 方法 del p1.sex print(p1.sex) #AttributeError: 'People' object has no attribute '_People__sex'

class Foo: def get_AAA(self): print('get的时候运行我啊') def set_AAA(self,value): print('set的时候运行我啊') def delete_AAA(self): print('delete的时候运行我啊') AAA=property(get_AAA,set_AAA,delete_AAA) #内置property三个参数与get,set,delete一一对应 f1=Foo() f1.AAA f1.AAA='aaa' del f1.AAA """ get的时候运行我啊 set的时候运行我啊 delete的时候运行我啊 """

class Goods: def __init__(self): # 原价 self.original_price = 100 # 折扣 self.discount = 0.8 @property def price(self): # 实际价格 = 原价 * 折扣 new_price = self.original_price * self.discount return new_price @price.setter def price(self, value): self.original_price = value @price.deleter def price(self): del self.original_price obj = Goods() print(obj.price) # 80.0 obj.price = 200 # 修改商品原价 print(obj.price) # 160.0 del obj.price # 删除商品原价

#实现类型检测功能 #第一关: class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name @property def name(self): return self.name p1=People('alex') #property自动实现了set和get方法属于数据描述符,比实例属性优先级高,所以你这写会触发property内置的set,抛出异常 #第二关:修订版 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('alex') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.__dict__) p1.name='egon' print(p1.__dict__) del p1.name print(p1.__dict__) #第三关:加上类型检查 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') if not isinstance(value,str): raise TypeError('必须是字符串类型') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('alex') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 p1.name=1

__init__

- 使用Python写面向对象的代码的时候我们都会习惯性写一个 __init__ 方法,__init__ 方法通常用在初始化一个类实例的时候。

- 下面是__init__最普通的用法了。但是__init__其实不是实例化一个类的时候第一个被调用的方法。

- 当使用 Persion(name, age) 来实例化一个类时,最先被调用的方法其实是 __new__ 方法。

class Person: def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age def __str__(self): return '<Person: {}({})>'.format(self.name, self.age) p1 = Person('张三', 24) print(p1) #<Person: 张三(24)>

__new__

- 其实__init__是在类实例被创建之后调用的,它完成的是类实例的初始化操作,而 __new__方法正是创建这个类实例的方法。

- __new__方法在类定义中不是必须写的,如果没定义的话默认会调用object.__new__去创建一个对象(因为创建类的时候默认继承的就是object)。

- 如果我们在类中定义了__new__方法,就是重写了默认的__new__方法,我们可以借此自定义创建对象的行为。

- 重写类的__new__方法来实现单例模式。

class A: def __init__(self): self.x = 1 print('in init function') def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print('in new function') return object.__new__(A) a = A() print(a.x) """ in new function in init function 1 """

class Person: def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print('调用__new__,创建类实例') return super().__new__(Person) def __init__(self, name, age): print('调用__init__,初始化实例') self.name = name self.age = age def __str__(self): return '<Person: {}({})>'.format(self.name, self.age) p1 = Person('张三', 24) print(p1) """ 调用__new__,创建类实例 调用__init__,初始化实例 <Person: 张三(24)> """

class Foo(object): def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): #__new__是一个类方法,在对象创建的时候调用 print ("excute __new__") return super(Foo,cls).__new__(cls) def __init__(self,value): #__init__是一个实例方法,在对象创建后调用,对实例属性做初始化 print ("excute __init") self.value = value f1 = Foo(1) print(f1.value) f2 = Foo(2) print(f2.value) #输出===: excute __new__ excute __init 1 excute __new__ excute __init 2 #====可以看出new方法在init方法之前执行 #必须注意的是,类的__new__方法之后,必须生成本类的实例才能自动调用本类的__init__方法进行初始化,否则不会自动调用__init__. ## 单例:即单个实例,指的是同一个类实例化多次的结果指向同一个对象,用于节省内存空间 #方式一: import threading class Singleton(): def __init__(self,name): self.name=name _instance_lock = threading.Lock() def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): with cls._instance_lock: if not hasattr(cls,'_instance'): cls._instance = super().__new__(cls) return cls._instance def task(i): Singleton(i) print(id(Singleton(i))) if __name__ == '__main__': for i in range(10): t = threading.Thread(target=task, args=(i,)) t.start() #方式二: import threading class Single(type): _instance_lock = threading.Lock() def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): with self._instance_lock: if not hasattr(self, '_instance'): self._instance = super().__call__(*args, **kwargs) return self._instance class Singleton(metaclass=Single): def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def task(i): Singleton(i) print(id(Singleton(i))) if __name__ == '__main__': for i in range(10): t = threading.Thread(target=task, args=(i,)) t.start() ############ 对类的结构进行改变的时候我们才要重写__new__这个方法 ############ 重写元类的__init__方法,而不是__new__方法来为元类增加一个属性。 #通过元类的__new__方法来也可以实现,但显然没有通过__init__来实现优雅,因为我们不会为了为实例增加一个属性而重写__new__方法。所以这个形式不推荐。 #########不推荐 class Singleton(type): def __new__(cls, name,bases,attrs): print ("__new__") attrs["_instance"] = None return super(Singleton,cls).__new__(cls,name,bases,attrs) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): if self._instance is None: self._instance = super(Singleton,self).__call__(*args, **kwargs) return self._instance class Foo(metaclass=Singleton): pass #在代码执行到这里的时候,元类中的__new__方法和__init__方法其实已经被执行了,而不是在Foo实例化的时候执行。且仅会执行一次。 foo1 = Foo() foo2 = Foo() print (Foo.__dict__) print (foo1 is foo2) # True ######### 推荐 class Singleton(type): def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs): print ("__init__") self.__instance = None super(Singleton,self).__init__(*args, **kwargs) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print ("__call__") if self.__instance is None: self.__instance = super(Singleton,self).__call__(*args, **kwargs) return self.__instance class Foo(metaclass=Singleton): pass #在代码执行到这里的时候,元类中的__new__方法和__init__方法其实已经被执行了,而不是在Foo实例化的时候执行。且仅会执行一次。 foo1 = Foo() foo2 = Foo() print (Foo.__dict__) #_Singleton__instance': <__main__.Foo object at 0x100c52f10> 存在一个私有属性来保存属性,而不会污染Foo类(其实还是会污染,只是无法直接通过__instance属性访问) print (foo1 is foo2) # True #方式三:定义一个类方法实现单例模式 class Mysql: __instance=None def __init__(self,host,port): self.host=host self.port=port @classmethod def singleton(cls): if not cls.__instance: cls.__instance=cls('127.0.0.1',3306) return cls.__instance obj1=Mysql('1.1.1.2',3306) obj2=Mysql('1.1.1.3',3307) print(obj1 is obj2) #False obj3=Mysql.singleton() obj4=Mysql.singleton() print(obj3 is obj4) #True #方式四:定义一个装饰器实现单例模式 def singleton(cls): #cls=Mysql _instance=cls('127.0.0.1',3306) def wrapper(*args,**kwargs): if args or kwargs: obj=cls(*args,**kwargs) return obj return _instance return wrapper @singleton # Mysql=singleton(Mysql) class Mysql: def __init__(self,host,port): self.host=host self.port=port obj1=Mysql() obj2=Mysql() obj3=Mysql() print(obj1 is obj2 is obj3) #True obj4=Mysql('1.1.1.3',3307) obj5=Mysql('1.1.1.4',3308) print(obj3 is obj4) #False ##### 不传参数是单列 传参数是对应的实例 class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): #定义类Mysql时就触发 # 事先先从配置文件中取配置来造一个Mysql的实例出来 self.__instance = object.__new__(self) # 产生对象 self.__init__(self.__instance, '127.0.0.1', 3306) # 初始化对象 # 上述两步可以合成下面一步 # self.__instance=super().__call__(*args,**kwargs) super().__init__(name,bases,dic) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #Mysql(...)时触发 if args or kwargs: # args或kwargs内有值 obj=object.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj return self.__instance class Mysql(metaclass=Mymeta): def __init__(self,host,port): self.host=host self.port=port obj1=Mysql() # 没有传值则默认从配置文件中读配置来实例化,所有的实例应该指向一个内存地址 obj2=Mysql() obj3=Mysql() print(obj1 is obj2 is obj3) #True obj4=Mysql('1.1.1.4',3307) obj5=Mysql('1.1.1.4',3307) print(obj4 is obj5) #False

__call__

- __call__ 方法的执行是由对象后加括号触发的,即:对象()。拥有此方法的对象可以像函数一样被调用。

- 构造方法的执行是由创建对象触发的,即:对象 = 类名()

- 而对于 __call__ 方法的执行是由对象后加括号触发的,即:对象() 或者 类()()

- 注意:__new__、__init__、__call__等方法都不是必须写的。

class Foo: def __init__(self): print("__init__") def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') obj = Foo() # 执行 __init__ obj() # 执行 __call__ Foo()() # 执行 __init__ 执行 __call__

class MyType(type): def __call__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print(cls) obj = cls.__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs) print('在这里面..') print('==========================') obj.__init__(*args, **kwargs) return obj class Foo(metaclass=MyType): def __init__(self): self.name = 'alex' print('123') f = Foo() #调用 print(f.name) """ <class '__main__.Foo'> 在这里面.. ========================== 123 alex """

''' 单例模式: 单例模式是一个软件的设计模式,为了保证一个类,无论调用多少次产生的实例对象, 都是指向同一个内存地址,仅仅只有一个实例(对象)! 五种单例: - 模块 - 装饰器 - 元类 - __new__ - 类方法: classmethod ''' class People: def __init__(self, name, age, sex): self.name = name self.age = age self.sex = sex # 调用三次相同的类,传递相同的参数,产生不同的三个实例 p1 = People('tank', 17, 'male') p2 = People('tank', 17, 'male') p3 = People('tank', 17, 'male') # print(p1 is p2 is p3) # 打开同一个文件的时候,链接MySQL数据库 ''' 伪代码 mysql_obj1 = MySQL(ip, port) mysql_obj2 = MySQL(ip, port) mysql_obj3 = MySQL(ip, port) ''' ''' 方式一: @classmethod ---> 通过类方法来实现单例 ''' class Foo(object): # 定义了一个类的数据属性, # 用于接收对象的实例,判断对象的实例是否只有一个 _instance = None # obj1 def __init__(self, name, age): self.name = name self.age = age @classmethod def singleton(cls, *args, **kwargs): # 判断类属性_instance是否有值,有代表已经有实例对象 # 没有则代表没有实例对象,则调用object的__init__获取实例对象 if not cls._instance: # object.__new__(cls): 创造对象 # 没有参数情况下 # cls._instance = object.__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs) # 有参数的情况下 cls._instance = cls(*args, **kwargs) # Foo() # 将已经产生的实例对象 直接返回 return cls._instance obj1 = Foo.singleton('tank', '123') obj2 = Foo.singleton('tank', '123') # print(obj1 is obj2) ''' 方式二: 元类 ''' class MyMeta(type): # 1、先触发元类里面的__init__ def __init__(self, name, base, attrs): # self --> Goo # *** 造空的对象, 然后赋值给了Goo类中的_instance类属性 self._instance = object.__new__(self) # 将类名、基类、类的名称空间,传给type里面的__init__ super().__init__(name, base, attrs) # type.__init__(self, name, base, attrs) # 2、当调用Goo类时,等同于调用了由元类实例化的到的对象 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): # 判断调用Goo时是否传参 if args or kwargs: init_args = args init_kwargs = kwargs # 1)通过判断限制了用于传入的参数必须一致,然后返回同一个对象实例 if init_args == args and init_kwargs == kwargs: return self._instance # 2) 若不是同一个实例,则新建一个对象,产生新的内存地址 obj = object.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj, *args, **kwargs) return obj return self._instance class Goo(metaclass=MyMeta): # Goo = MyMeta(Goo) # _instance = obj def __init__(self, x): self.x = x g1 = Goo('1') g2 = Goo('1') # print(g1 is g2) # True ''' 方式三: __new__实现 ---> 通过调用类方法实例化对象时,自动触发的__new__来实现单例 ''' class Aoo(object): _instance = None def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): if not cls._instance: cls._instance = object.__new__(cls) return cls._instance a1 = Aoo() a2 = Aoo() # print(a1 is a2) # True ''' 方式四: 装饰器实现 ---> 通过调用类方法实例化对象时,自动触发的__new__来实现单例 ''' # 单例装饰器 def singleton_wrapper(cls): # cls ---> Too # 因为装饰器可以给多个类使用,所以这里采用字典 # 以类作为key, 实例对象作为value值 _instance = { # 伪代码: 'Too': Too的示例对象 } def inner(*args, **kwargs): # 若当前装饰的类不在字典中,则实例化新类 # 判断当前装饰的Too类是否在字典中 if cls not in _instance: # obj = cls(*args, **kwargs) # return obj # 不在,则给字典添加 key为Too, value为Too()---> 实例对象 # {Too: Too(*args, **kwargs)} _instance[cls] = cls(*args, **kwargs) # return 对应的实例对象cls(*args, **kwargs) return _instance[cls] return inner @singleton_wrapper # singleton_wrapper(Too) class Too(object): pass t1 = Too() t2 = Too() # print(t1 is t2) # True ''' 方式五: 模块导入实现 ''' import cls_singleton s1 = cls_singleton.instance s2 = cls_singleton.instance print(s1 is s2) # True #######cls_singleton.py class Foo(object): pass instance = Foo()

__doc__

- 它类的描述信息

- 该属性无法继承给子类

class Foo: #我是描述信息 pass class Bar(Foo): pass print(Bar.__doc__) #None 该属性无法继承给子类

__annotations__

def test(x:int,y:int)->int: return x+y print(test.__annotations__) #{'x': <class 'int'>, 'y': <class 'int'>, 'return': <class 'int'>}

描述符(__get__,__set__,__delete__)

- 描述符本质:

- 就是一个新式类,在这个新式类中,至少实现了__get__(),__set__(),__delete__()中的一个,这也被称为描述符协议

- __get__()调用一个属性时,触发

- __set__()为一个属性赋值是,触发

- __delete__()采用del删除属性时,触发

- 描述符的作用:

- 是用来代理另外一个类的属性的(必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能定义到构造函数中)

- 描述符分两种:

- 数据描述符:至少实现了__get__()和__set__()

- 非数据描述符:没有实现__set__()

- 注意事项:

- 描述符本身应该定义成新式类,被代理的类也应该是新式类

- 必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能为定义到构造函数中

- 要严格遵循该优先级,优先级由高到底分别是

- 类属性

- 数据描述符

- 实例属性

- 非数据描述符

- 找不到的属性触发__getattr__()

- 描述符总结:

- 描述符是可以实现大部分python类特性中的底层魔法,包括@classmethod,@staticmethd,@property甚至是__slots__属性

- 描述符是很多高级库和框架的重要工具之一,描述符通常是使用到装饰器或者元类的大型框架中的一个组件

class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('触发get') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('触发set') def __delete__(self, instance): print('触发delete') #包含这三个方法的新式类称为描述符,由这个类产生的实例进行属性的调用/赋值/删除,并不会触发这三个方法 f1=Foo() f1.name='egon' f1.name del f1.name #疑问:何时,何地,会触发这三个方法的执行 #描述符分两种 #1:数据描述符:至少实现了__get__()和__set__() class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') #2:非数据描述符:没有实现__set__() class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get')

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') #描述符Int class Int: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Int调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Int设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Int删除...') class People: name=Str() age=Int() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age #何地?:定义成另外一个类的类属性 #何时?:且看下列演示 p1=People('alex',18) #描述符Str的使用 p1.name p1.name='egon' del p1.name #描述符Int的使用 p1.age p1.age=18 del p1.age #我们来瞅瞅到底发生了什么 print(p1.__dict__) print(People.__dict__) #补充 print(type(p1) == People) #type(obj)其实是查看obj是由哪个类实例化来的 print(type(p1).__dict__ == People.__dict__)

类属性>数据描述符

类属性>数据描述符

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') class People: name=Str() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age p1=People('egon',18) #如果描述符是一个数据描述符(即有__get__又有__set__),那么p1.name的调用与赋值都是触发描述符的操作,于p1本身无关了,相当于覆盖了实例的属性 p1.name='egonnnnnn' p1.name print(p1.__dict__)#实例的属性字典中没有name,因为name是一个数据描述符,优先级高于实例属性,查看/赋值/删除都是跟描述符有关,与实例无关了 del p1.name

实例属性>非数据描述符

实例属性>非数据描述符

class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo实现了get和set方法,因而比实例属性有更高的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是描述符的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房' class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个非数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo没有实现set方法,因而比实例属性有更低的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是实例自己的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房'

非数据描述符>找不到

非数据描述符>找不到

class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3231.3) #调用 print(p1.__dict__) p1.name #赋值 print(p1.__dict__) p1.name='egonlin' print(p1.__dict__) #删除 print(p1.__dict__) del p1.name print(p1.__dict__)

class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary #疑问:如果我用类名去操作属性呢 People.name #报错,错误的根源在于类去操作属性时,会把None传给instance #修订__get__方法 class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary print(People.name) #完美,解决

class Str: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): #如果不是期望的类型,则抛出异常 raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name',str) #新增类型限制str def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People(123,18,3333.3)#传入的name因不是字符串类型而抛出异常

类型限制4

类型限制4 类型限制5

类型限制5

def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>') return cls @decorate #无参:People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3333.3)

def typeassert(**kwargs): def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>',kwargs) return cls return decorate @typeassert(name=str,age=int,salary=float) #有参:1.运行typeassert(...)返回结果是decorate,此时参数都传给kwargs 2.People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3333.3)

自己做一个@property

自己做一个@property 实现延迟计算功能

实现延迟计算功能 一个小的改动,延迟计算的美梦就破碎了

一个小的改动,延迟计算的美梦就破碎了

class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s' %cls.name) People.say_hi() p1=People() p1.say_hi() #疑问,类方法如果有参数呢,好说,好说 class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner,*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls,msg): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s %s' %(cls.name,msg)) People.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼') p1=People() p1.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼')

class StaticMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: @StaticMethod# say_hi=StaticMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(x,y,z): print('------>',x,y,z) People.say_hi(1,2,3) p1=People() p1.say_hi(4,5,6)

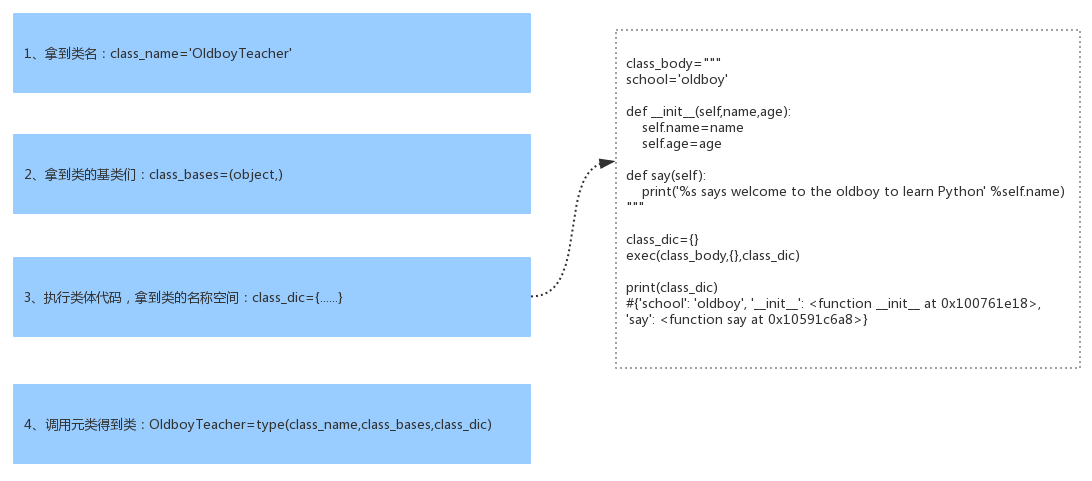

metaclass

- 元类是类的类,是类的模板

- 元类是用来控制如何创建类的,正如类是创建对象的模板一样

- 元类的实例为类,正如类的实例为对象(f1对象是Foo类的一个实例,Foo类是 type 类的一个实例)

- type是python的一个内建元类,用来直接控制生成类,python中任何class定义的类其实都是type类实例化的对象。

#type元类,是所有类的类,利用type模拟class关键字的创建类的过程 class Bar2: x=1 def run(self): print('%s is runing' %self.name) print(Bar2.__bases__) print(Bar2.__dict__) #用type模拟Bar2 def run(self): print('%s is runing' %self.name) class_name='Bar' bases=(object,) class_dic={ 'x':1, 'run':run } Bar=type(class_name,bases,class_dic) print(Bar) #<class '__main__.Bar'> print(type(Bar)) #<class 'type'> print(Bar.__bases__) print(Bar.__dict__) #就是新建了一个空类 class Spam2: pass print(Spam2) print(Spam2.__bases__) print(Spam2.__dict__) #用type模拟Spam2 Spam=type('Spam',(),{}) print(Spam) print(Spam.__bases__) print(Spam.__dict__)

class Poo(metaclass=type): #就是执行了 type('Poo',(object,),{'x':1,'run':...}) x=1 def run(self): print('running') #__init__ class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): #这的self就是Foo类 for key in class_dic: if not callable(class_dic[key]):continue if not class_dic[key].__doc__: raise TypeError('你没写注释,赶紧去写') # type.__init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic) class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): #就是执行了 Foo=Mymeta('Foo',(object,),{'x':1,'run':...}) x=1 def run(self): 'run function' print('running') #__call__ class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): pass def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):# print(self) 这的self就是Foo类 obj=self.__new__(self) #建一个空对象 self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) #注意参数obj obj.name='tom' return obj #把对象返回 class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): x=1 def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #obj.name='tom' def run(self): print('running') f=Foo('tom') print(f) print(f.name)

""" exec:3个参数 参数 1:包含一系列python代码的字符串 参数 2:全局作用域(字典形式),如果不指定,默认为globals() 参数 3:局部作用域(字典形式),如果不指定,默认为locals() 可以把exec命令的执行当成是一个函数的执行,会将执行期间产生的名字存放于局部名称空间中 """ g={ 'x':1, 'y':2 } l={} exec(''' global x,z x=100 z=200 m=300 ''',g,l) print(g) #{'x': 100, 'y': 2,'z':200,......} print(l) #{'m': 300}

class Foo: def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print(self) print(args) print(kwargs) obj=Foo() #1、要想让obj这个对象变成一个可调用的对象,需要在该对象的类中定义一个方法__call__方法,该方法会在调用对象时自动触发 #2、调用obj的返回值就是__call__方法的返回值 res=obj(1,2,3,x=1,y=2) """ <__main__.Foo object at 0x0000000000B0BEB8> (1, 2, 3) {'x': 1, 'y': 2} """

class OldboyTeacher(object): school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) t1=OldboyTeacher('egon',18) print(type(t1)) #查看对象t1的类是<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> print(type(OldboyTeacher)) # 结果为<class 'type'>,证明是调用了type这个元类而产生的OldboyTeacher,即默认的元类为type """ 一: python中一切皆为对象。 所有的对象都是实例化或者说调用类而得到的(调用类的过程称为类的实例化),比如对象t1是调用类OldboyTeacher得到的 元类-->实例化-->类OldboyTeacher-->实例化-->对象t1 二: class关键字创建类的流程分析: 用class关键字定义的类本身也是一个对象,负责产生该对象的类称之为元类(元类可以简称为类的类),内置的元类为type class关键字在帮我们创建类时,必然帮我们调用了元类OldboyTeacher=type(...),那调用type时传入的参数是什么呢? 必然是类的关键组成部分,一个类有三大组成部分,分别是 1、类名class_name='OldboyTeacher' 2、基类们class_bases=(object,) 3、类的名称空间class_dic,类的名称空间是执行类体代码而得到的 调用type时会依次传入以上三个参数 综上,class关键字帮我们创建一个类应该细分为以下四个过程: 1、拿到类名:class_name='OldboyTeacher' 2、拿到类的基类们:class_bases=(object,) 3、执行类体代码,拿到类的名称空间:class_dic={...} 4、调用元类得到类:OldboyTeacher=type(class_name,class_bases,class_dic) 三: 自定义元类控制类OldboyTeacher的创建: 一个类没有声明自己的元类,默认他的元类就是type,除了使用内置元类type, 我们也可以通过继承type来自定义元类,然后使用metaclass关键字参数为一个类指定元类 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 pass class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): # OldboyTeacher=Mymeta('OldboyTeacher',(object),{...}) school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) """ 四: 自定义元类可以控制类的产生过程,类的产生过程其实就是元类的调用过程, 即OldboyTeacher=Mymeta('OldboyTeacher',(object),{...}), 调用Mymeta会先产生一个空对象OldoyTeacher, 然后连同调用Mymeta括号内的参数一同传给Mymeta下的__init__方法,完成初始化,于是我们可以 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): # print(self) #<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> # print(class_bases) #(<class 'object'>,) # print(class_dic) #{'__module__': '__main__', '__qualname__': 'OldboyTeacher', 'school': 'oldboy', '__init__': <function OldboyTeacher.__init__ at 0x102b95ae8>, 'say': <function OldboyTeacher.say at 0x10621c6a8>} super(Mymeta, self).__init__(class_name, class_bases, class_dic) # 重用父类的功能 if class_name.islower(): raise TypeError('类名%s请修改为驼峰体' %class_name) if '__doc__' not in class_dic or len(class_dic['__doc__'].strip(' \n')) == 0: raise TypeError('类中必须有文档注释,并且文档注释不能为空') class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): # OldboyTeacher=Mymeta('OldboyTeacher',(object),{...}) """ 类OldboyTeacher的文档注释 """ school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) """ 五: 自定义元类控制类OldboyTeacher的调用: 储备知识:__call__ 调用一个对象,就是触发对象所在类中的__call__方法的执行,如果把OldboyTeacher也当做一个对象, 那么在OldboyTeacher这个对象的类中也必然存在一个__call__方法 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print(self) #<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> print(args) #('egon', 18) print(kwargs) #{} return 123 class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) # 调用OldboyTeacher就是在调用OldboyTeacher类中的__call__方法 # 然后将OldboyTeacher传给self,溢出的位置参数传给*,溢出的关键字参数传给** # 调用OldboyTeacher的返回值就是调用__call__的返回值 t1=OldboyTeacher('egon',18) print(t1) #123 """ 六: 默认地,调用t1=OldboyTeacher('egon',18)会做三件事 1、产生一个空对象obj 2、调用__init__方法初始化对象obj 3、返回初始化好的obj 对应着,OldboyTeacher类中的__call__方法也应该做这三件事 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> #1、调用__new__产生一个空对象obj obj=self.__new__(self) # 此处的self是类OldoyTeacher,必须传参,代表创建一个OldboyTeacher的对象obj #2、调用__init__初始化空对象obj self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) #3、返回初始化好的对象obj return obj class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) t1=OldboyTeacher('egon',18) print(t1.__dict__) #{'name': 'egon', 'age': 18} """ 七: 上例的__call__相当于一个模板,我们可以在该基础上改写__call__的逻辑从而控制调用OldboyTeacher的过程, 比如将OldboyTeacher的对象的所有属性都变成私有的 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> #1、调用__new__产生一个空对象obj obj=self.__new__(self) # 此处的self是类OldoyTeacher,必须传参,代表创建一个OldboyTeacher的对象obj #2、调用__init__初始化空对象obj self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) # 在初始化之后,obj.__dict__里就有值了 obj.__dict__={'_%s__%s' %(self.__name__,k):v for k,v in obj.__dict__.items()} #3、返回初始化好的对象obj return obj class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) t1=OldboyTeacher('egon',18) print(t1.__dict__) #{'_OldboyTeacher__name': 'egon', '_OldboyTeacher__age': 18} """ 八: 再看属性查找: 上例中涉及到查找属性的问题,比如self.__new__ 结合python继承的实现原理+元类重新看属性的查找应该是什么样子呢??? 在学习完元类后,其实我们用class自定义的类也全都是对象(包括object类本身也是元类type的 一个实例,可以用type(object)查看), 我们学习过继承的实现原理,如果把类当成对象去看,将下述继承应该说成是:对象OldboyTeacher继承对象Foo,对象Foo继承对象Bar,对象Bar继承对象object """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 n=444 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> obj=self.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj class Bar(object): n=333 class Foo(Bar): n=222 class OldboyTeacher(Foo,metaclass=Mymeta): n=111 school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) print(OldboyTeacher.n) #自下而上依次注释各个类中的n=xxx,然后重新运行程序,发现n的查找顺序为OldboyTeacher->Foo->Bar->object->Mymeta->type """ 九: 于是属性查找应该分成两层,一层是对象层(基于c3算法的MRO)的查找,另外一个层则是类层(即元类层)的查找 #查找顺序: #1、先对象层:OldoyTeacher->Foo->Bar->object #2、然后元类层:Mymeta->type 分析下元类Mymeta中__call__里的self.__new__的查找 """ class Mymeta(type): n=444 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.OldboyTeacher'> obj=self.__new__(self) print(self.__new__ is object.__new__) #True class Bar(object): n=333 # def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): # print('Bar.__new__') class Foo(Bar): n=222 # def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): # print('Foo.__new__') class OldboyTeacher(Foo,metaclass=Mymeta): n=111 school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) # def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): # print('OldboyTeacher.__new__') OldboyTeacher('egon',18) #触发OldboyTeacher的类中的__call__方法的执行,进而执行self.__new__开始查找 """ 十: 总结,Mymeta下的__call__里的self.__new__在OldboyTeacher、Foo、Bar里都没有找到__new__的情况下, 会去找object里的__new__,而object下默认就有一个__new__,所以即便是之前的类均未实现__new__, 也一定会在object中找到一个,根本不会、也根本没必要再去找元类Mymeta->type中查找__new__ 我们在元类的__call__中也可以用object.__new__(self)去造对象 但我们还是推荐在__call__中使用self.__new__(self)去创造空对象, 因为这种方式会检索三个类OldboyTeacher->Foo->Bar,而object.__new__则是直接跨过了他们三个 """ class Mymeta(type): #只有继承了type类才能称之为一个元类,否则就是一个普通的自定义类 n=444 def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): obj=type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) # 必须按照这种传值方式 print(obj.__dict__) # return obj # 只有在返回值是type的对象时,才会触发下面的__init__ return 123 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): print('run。。。') class OldboyTeacher(object,metaclass=Mymeta): #OldboyTeacher=Mymeta('OldboyTeacher',(object),{...}) n=111 school='oldboy' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def say(self): print('%s says welcome to the oldboy to learn Python' %self.name) print(type(Mymeta)) #<class 'type'> """ 产生类OldboyTeacher的过程就是在调用Mymeta,而Mymeta也是type类的一个对象,那么Mymeta之所以可以调用,一定是在元类type中有一个__call__方法 该方法中同样需要做至少三件事: class type: def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.Mymeta'> obj=self.__new__(self,*args,**kwargs) # 产生Mymeta的一个对象 self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj """

在元类中控制把自定义类的数据属性都变成大写

在元类中控制把自定义类的数据属性都变成大写

""" 练习二:在元类中控制自定义的类无需__init__方法 1.元类帮其完成创建对象,以及初始化操作; 2.要求实例化时传参必须为关键字形式,否则抛出异常TypeError: must use keyword argument 3.key作为用户自定义类产生对象的属性,且所有属性变成大写 """ class Mymetaclass(type): # def __new__(cls,name,bases,attrs): # update_attrs={} # for k,v in attrs.items(): # if not callable(v) and not k.startswith('__'): # update_attrs[k.upper()]=v # else: # update_attrs[k]=v # return type.__new__(cls,name,bases,update_attrs) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): if args: raise TypeError('must use keyword argument for key function') obj = object.__new__(self) #创建对象,self为类Foo for k,v in kwargs.items(): obj.__dict__[k.upper()]=v return obj class Chinese(metaclass=Mymetaclass): country='China' tag='Legend of the Dragon' #龙的传人 def walk(self): print('%s is walking' %self.name) p=Chinese(name='egon',age=18,sex='male') print(p.__dict__)

class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): #控制类Foo的创建 super(Mymeta,self).__init__(class_name,class_bases,class_dic) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #控制Foo的调用过程,即Foo对象的产生过程 obj = self.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj, *args, **kwargs) obj.__dict__={'_%s__%s' %(self.__name__,k):v for k,v in obj.__dict__.items()} return obj class Foo(object,metaclass=Mymeta): # Foo=Mymeta(...) def __init__(self, name, age,sex): self.name=name self.age=age self.sex=sex obj=Foo('egon',18,'male') print(obj.__dict__)