Pre-lab Reading

This exercise is designed to teach the principles of predator–prey relationships and their impact on ecological communities.

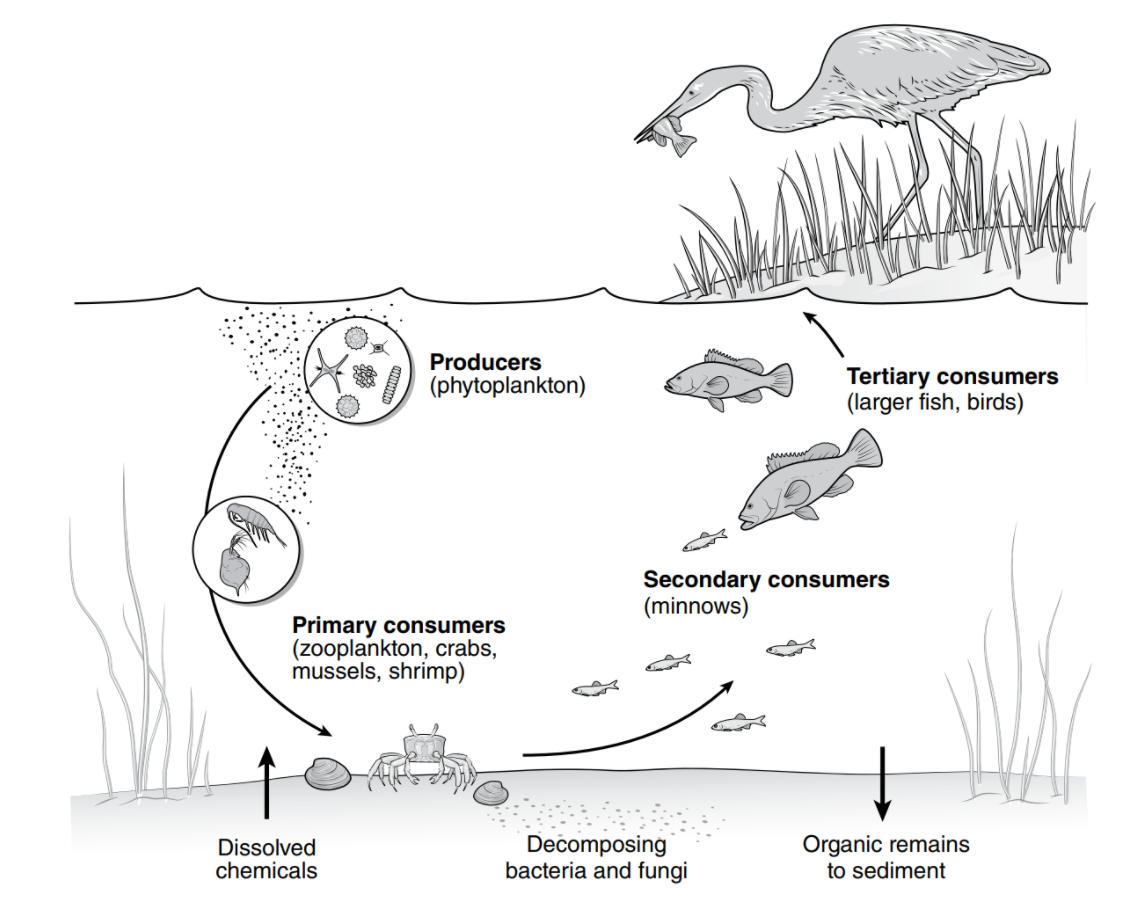

Predators are animals that prey upon other animals. Predators can play at least three critical roles in shaping the structure of ecological communities. They can restrict prey distribution or reduce abundance, which can lead to greater species diversity. The presence and absence of predators can alter the structure of an ecological community. For example, in the absence of predators, herbivores are able to feed and increase in abundance, resulting in a decrease of available plant material. However, when predators are present, herbivore abundance can be reduced, increas-ing plant species richness and/or abundance. These interactions can be expressed in a trophic model (see Figure 8.1). In addition, predation can be a selective force that leads to predator–prey coevolution.

The behavior of foraging for food involves four steps: search, recognition, capture, and handling the captured food. Predators search the environment for acceptable prey items, and consequently predator adaptations to improve foraging success include better visual, olfactory, tactile, and auditory acuity, development of search images, and limiting searches to prey-rich habitats. Most predators quickly learn which prey types are optimal for foraging and which are inedible. Since predators must capture prey to eat, many have adaptations to improve capture efficiency, such as improved motor skills and appendage modification for improved handling of their prey. Finally, predators must handle prey by efficiently subduing them. Adaptations that promote handling efficiency include improved foraging appendages to reduce the probability of injury and physiological specialization on otherwise poison-ous prey. Predators can also improve foraging efficiency by learned avoidance, a behavior in which predators learn to recognize poisonous or distasteful species by remembering adverse reactions from attempted predation events.

Not surprisingly, prey species don’t want to be eaten by predators. Therefore prey species have evolved many mechanisms to counter predator efficiency. Prey can be difficult to locate because of cryptic

coloration or forms. Prey can also be difficult to locate because they are usually scattered throughout the environment. In some cases prey species exhibit mimicry and have adapted to appear similar to a poisonous or dangerous species so that a potential predator will not eat them. Many prey species have also developed defensive mechanisms to escape quickly and to reduce the handling efficiency of predators. Some of these defenses include spines, tough cuticles, and toxins, which make them poisonous or unpalatable.

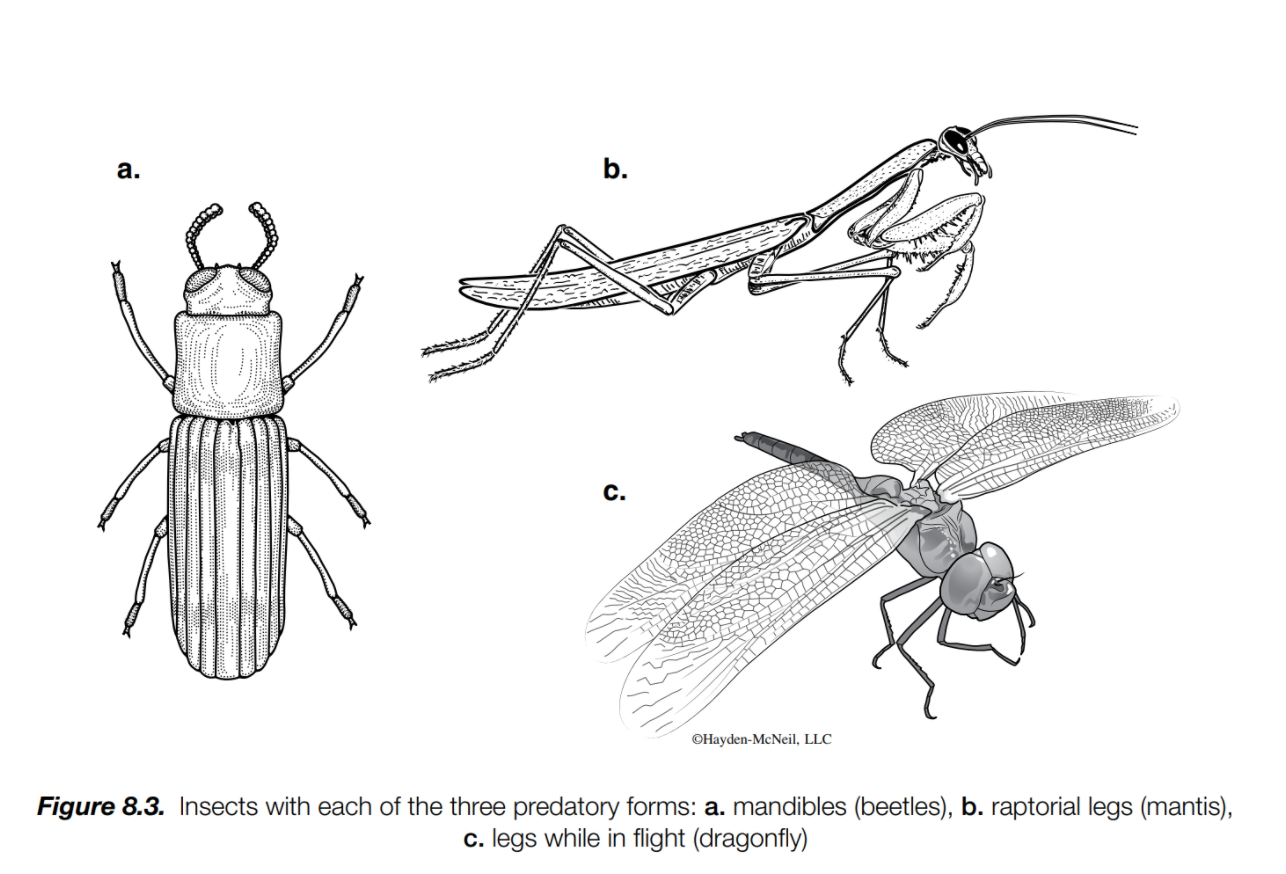

Insects provide some of the most dramatic examples of predator–prey coevolution and are ideal subjects for illustrating the principles of predator–prey interactions and their role in shaping eco-logical communities. Three particular predator forms are common among insects. Many insects, such as ground beetles and tiger beetles, kill their prey with their mandibles. Another method used by insects includes using enlarged legs to grab and subdue prey. Praying mantises, water bugs, and ambush bugs are among the predatory insects that use this method to capture prey. Aerial preda-tors, such as dragonflies and robber flies, grasp prey with their legs while in flight. All three of these methods are used by generalist species that feed on any arthropods that they can find and capture.

Insects use a variety of defenses against predators. Defenses include being cryptic or polymorphic, being able to escape rapidly, being armored, and being poisonous. Additionally, many edible species gain protection from predators by mimicking the appearance of poisonous species. Insect predators can become ill from eating poisonous prey and can learn to avoid prey species that appear similar to poisonous species.

A predator’s ability to catch prey is also limited by other factors such as limited time available for prey searching, limited stomach size, and time needed for digestion. Extrinsic factors include competition with other predators and environmental disturbances. Often, when an environment is disturbed, such as by flooding, fire, pesticide use, or farming, predator–prey relationships change. If few predators are in the environment, herbivores can reproduce rapidly to reach high local densities. This effect may be countered by a numerical increase of predators moving to the area. When there are many predators and abundant prey available, the predators capture as many prey as quickly as possible. As predation causes prey to become more limited, competing predators may interact directly, leading to injuries or limited predatory success. When the environment becomes more stable, competition returns the community to an equilibrium of predator–prey species. Resource limitation due to in-creased competition, carrying capacity, can also regulate population sizes of prey.

Online Lab 8: Competition and Predation

Your instructor will provide you with a list of possible nature documentaries to view for this exercise. You will identify and examine four examples of predator-prey interactions in the documentary (you may watch multiple documentaries if you wish). For each of the four interactions, fill out the datasheet and answer the questions. Each table and associated questions are worth 5 points